INGE RAPOPORT

Back in June I said I'd give you more detail on the story of extraordinary German centenarian Dr Inge Rapoport. I was reporting from Germany where the University of Hamburg awarded Dr Rapoport the medical degree denied her by the Nazis in 1938. And it wasn't simply an award. She had to earn it, doing an exam to defend her thesis, at age 102!

Ingeborg Syllum- Rapoport is another of the remarkable women I've met through this project. She’s sharp as a tack despite her age. She's also gracious, interesting, fascinating actually, with a life story that blends many of the strands of 20th century history. Nazism. Communism. McCarthyism. Migration. And a major motion picture love story.

And at the end of this post, a recipe for that most German dessert, apple cake.

All of life is here :-)

Personal connection

You can listen to a radio version of this story here. This is the documentary that I made for The Current, a programme on Canadian CBC, about Dr Rapoport – and my own grandmother.

You see I have a personal interest in this story of restitution. Inge Rapoport’s experience parallels that of my grandmother Hilde Jacobson, my mother's mother, who was studying medicine in Germany in the 1930’s.

And it's only while working on this story that I discovered that both women were studying at the University of Hamburg!

My German grandmother

Inge Rapoport and Grandmother Hilde were just 2 years apart at the Hamburg Medical school.

Neither woman completed her degree… the Nazis wouldn't let them.

My grandmother because she was Jewish; Inge Rapoport because her mother was Jewish.

Hamburg Medical School June 2015

It was a warm day on the cusp of the Northern summer when I arrived at the Hamburg Medical school this June for Inge Rapoport’s award ceremony. I was struck by the beautiful grounds, with their gracious buildings, noble trees, and seats, statues and flowering bushes.

I imagined my grandmother walking to class between these same buildings, past these same trees, and I stopped to look at shining cobblestones on the path. They turned out to be what are known as Stolperstein – from the German for stumbling block - and they are memorials for victims of Nazism.

On her way into the hall, Dr Inge Rapoport saw the names of her Jewish professors on these plaques in the floor, and remembered their sad fates.

“They had to emigrate. One of my professors fought in WWI and had a medal, he felt a real German. He was forced to leave, never ever gave a lecture again. He emigrated to Sweden. And there with his wife he committed suicide, the two of them together. Yes, terrible.”

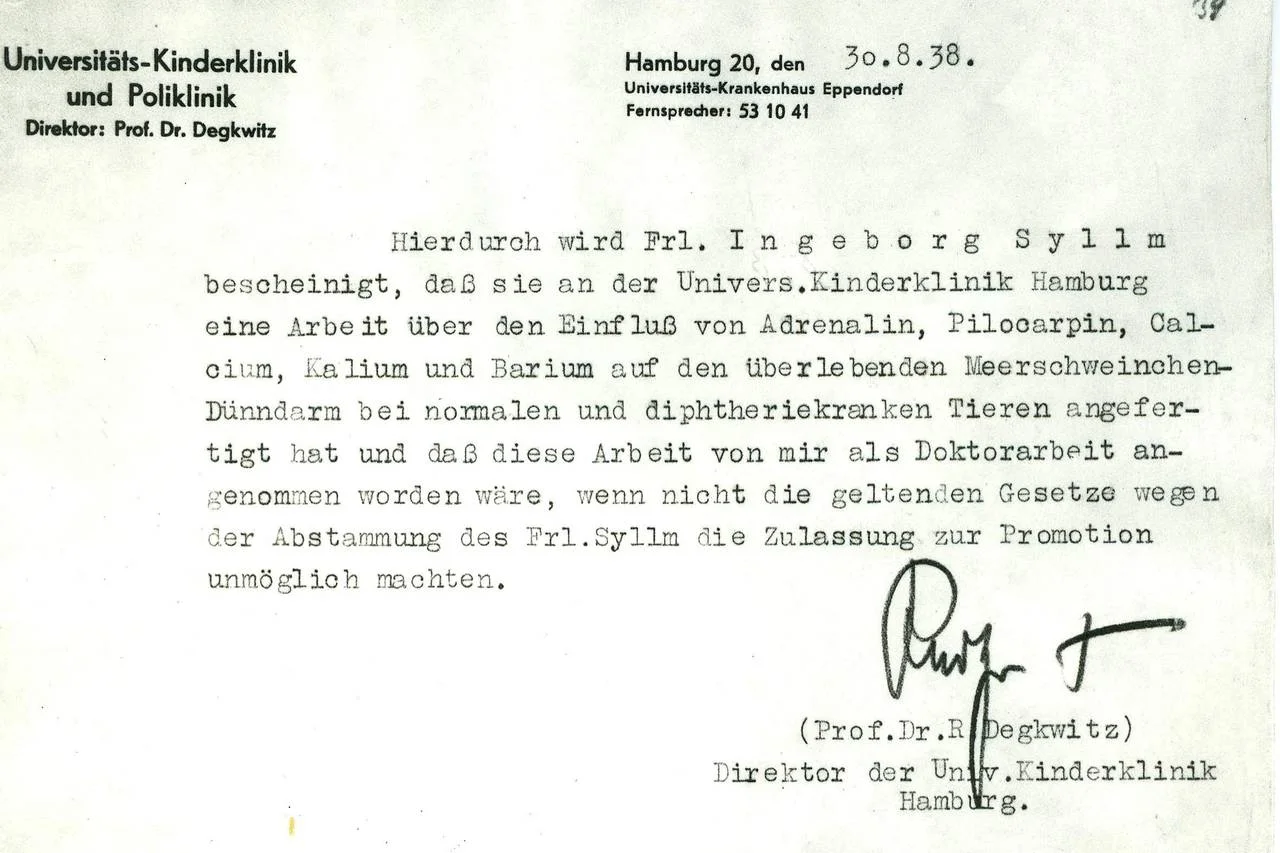

1938

This was the atmosphere when a young Inge Rapoport was completing her degree. She did her exams, and wrote her thesis on diptheria in children. Her supervisor passed her. But by then it was 1938 and the Nazis were tightening their control.

There would be no degree for the 26 year old Protestant woman, nor for the many other students like her, Christians with Jewish backgrounds.

Inge Raoport

"It was terrible. The Dean said there must have been 38 people who were in the same condition, partly Jewish, but I don’t know a single person, never met them, I was absolutely isolated from the other Jewish suffering people. My feeling for being Jewish is for sharing the same fate. And I stand for that.”

Award ceremony

Once inside the University Hall, there were TV cameras and hundreds of people: children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, friends, former colleagues, former students, officials, and other well-wishes. All wanted to be part of the historic day.

Below: Dr Rapoport with the Dean of the Hamburg Medical School and one of the Scientific examiners.

There was a buzz before the star student walked in – slowly.

Wearing sandals and socks, and walking with a stick, Inge was a like centenarian rock star.

But this elegant ceremony, which felt so simple and right, almost didn’t happen. The university which dangled the offer before Inge and her family soon found it couldn't fulfil it.

OBSTACLES

In her home in the Berlin garden suburb of Pankow, Inge Rapoport explained the process.

First of all, when Hamburg University approached her, Inge had to be talked into accepting the award.

“It was the idea of the university, it was not for my personal sake. I don’t need a doctor’s title any more. I got better titles after that. I became an MD in the US, I was a professor in East Germany, it’s 40 years since I finished my profession, so I didn't care. But I did care for all the others who had a similar fate, probably much worse, because I was lucky and they weren't and for them I do it, including for your grandmother! That’s why I gave you a special talk this morning...”

She blind sided me with that reference to my grandmother. I was almost surprised by how touched I was for her to include her in that way... and had to swallow hard so as not to tear up as I listened to the rest of Inge’s amazing story.

Brooklyn

In 1938, after Hamburg medical school refused to award her her degree she decided to leave Germany. And she was lucky - she could.

American relatives signed for her and she obtained a US visa. In 1938, she sailed for New York, alone, and virtually penniless. But she was safe, and began retraining as a doctor.

“I got a job almost immediately, in Brooklyn, how was that possible I don’t even know, it was just luck.”

London

My grandmother Hilde was also lucky. In 1939 – just months before World War Two began - she escaped to London. A British doctor kindly took in a German refugee. My grandmother worked as her housekeeper.

She had a baby – my mother – and later worked as a nurse. She never got the chance to train as a doctor again. My mother says that rankled all her life.

But Inge did go on to be a doctor, in the US.

“I was just lucky, very lucky, and of course conditions in US much kinder to immigrants than England was.”

Love story

On a ward round at an American hospital, Inge met a physician named Samuel Rapoport.

“I still remember the moment when I met him. It was like a thunderbolt!” says Inge. “I think he just thought that girl is cross-eyed. I always kidded him about that, because I liked to hear him say ‘No, it wasn't like that!’ ”

Sam Rapoport was a Jewish immigrant from Europe and a politically active socialist. When he proposed to Inge, he told her that his priorities were socialism and science and that she would only come third on the list. Luckily by then she had become a socialist too… and that didn't seem too daunting.

“I think my whole life since I met my husband was a love story. Up to now. I still love him and it was a great thing. That’s why the whole difficulties of my life, and there were many difficult things, but I never felt it like that, I was always happy, he was a wonderful man, an interesting man, with a wider vision of the world, and history, and what’s going to happen in the future.”

McCarthyism

But their views spelt trouble in the 1950s. America was going though the anti-Communist upheavals of the McCarthy era and after 12 years, the Rapoports were chased out of the US. Inge was devastated.

“That was my new home, I had intended to stay there, and every time I go back to the United States I still have a painful feeling inside myself," she says sadly.

communism

Inge and her husband ended up back in Germany - Communist East Germany this time.

Inge wanted to build Socialism. She also built a glittering career. She became a professor, and the first Neonatologist in East Germany, winning the nation's pre-eminent Science Award, their equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

She’s lived there ever since. (In the same house she and her family moved into in the 1950s. Like many of the grandmothers in this project, she hunkered down in her first home and stayed put.) And it was there that many years later she caught the attention of the Dean of the Hamburg medical school.

By accident really…

Two years ago, Dr Uwe Koch-Gromus discovered that Inge had been refused her degree at his university.

“It was by chance… I learned about it when professor Rapoport became 100 years old. It was a big event in Berlin. So I asked myself, why no one cared for that in 75 years?” the Dean of the Hamburg Medical School explains

He figured he just had to get his hands on Inge’s original thesis, and how hard could that be? As it turned out, the thesis wasn't to be found anywhere in the University and Inge couldn't locate it either.

“I can’t find it anywhere!” she wailed. “It must be here in the house.”

When I reminded her that it was a long time since 1938, she wasn't comforted.

“Yes, but it survived all the movings, I know I had it about 2 years after my husband died, I held it in my hands!”

Rules, rules, rules

Inge had a certificate from the professor who supervised her thesis and who accepted it. And another from the then Dean of the medical faculty, saying he’d received it.

But that wasn't enough. The Dean says he was hemmed in by his administrative rules.

So I asked him what I thought was the logical question. Had he maybe thought of awarding her an honorary degree?

“Yes. But I found it was not adequate, and nor did she, she didn't want that," Professor Koch-Gromus explained.

I wasn't sure I’d heard right. She didn't want it?

Then Inge explained that she didn't need an honourary degree - she had real medical degrees! That wasn't the purpose of the exercise.

“No, for what do I need an honourary degree? For my suffering under the Nazis? No! He didn't want it, and I didn't want it, we agreed completely on that," was Inge's response.

"And that is fully in line with her straight character,” says Professor Koch-Gromus approvingly.

The two agreed that the best way forward was for Inge to do an oral examination; that at 102 years old, she would update her thesis on diphtheria and re-present it.

No Short-cuts

Her daughter, Susan Richter – also a doctor – says her mother was adamant that she didn't want any short-cuts or concessions.

“She wanted that the oral examination would be a real examination. She was preparing herself and she really wanted to be good. I said it doesn't matter they just have to make a gesture, even something token will do, you don’t have to be afraid of it. But she was really afraid of it,” says Susan Richter.

It was frightening, because though Inge is incredibly sharp, she hasn't escaped all the problems of age.

“I’m practically blind. I can’t read, I can hardly see you.”

So Inge looked for a creative solution to not being able to read up for herself.

“I had students of mine, and my daughter-in-law, both bio-chemists and they googled for me,” she said.

It was done by phone.

“Calls, questions, answers, asked again, other things around the topic, so I learned a lot, and the learning was fun again," says Inge happily.

The date for the oral exam was set for May 2015, and the venue was Inge’s home in Berlin.

But as that day approached, Susan says her her mother remained worried about every little detail.

“She said – ‘What shall I do? I can’t give the examiners sandwiches because then it’s not an examination... you don’t get sandwiches in an exam.’ And I read in the newspaper afterwards a comment from the Dean: "We only got water!' ” Susan laughs.

D-Day

Finally the day of the exam arrived. Susan was on hand when the 3 examiners sat down, but in a room outside at inge's request.

“First they asked me if there’s anything I remembered from the original work. So I told them as much as I remember after 70 years. They were satisfied, and kind of amazed that I remembered things, and then I criticised my own work and asked deeper questions than I could have at that time," said Inge.

But Inge never relaxed into it. It didn't become fun.

“No I was terribly nervous, I was nervous for myself, I didn't want to be bad, and I didn't want to be a disappointment to the Dean, so I had 2 sources of excitement. And I did much worse than I could have done.”

Amazing. Inge's upset because she could have done better!!!

Inge Rapoport, in the 'examination chair' in her Berlin sitting room.

In fact, Dr Uwe Koch-Gromus says he and the examiners marvelled at Inge's clarity, accuracy and fluency – talking them through all the scientific advances without notes (of course, since she can’t see.)

“We were so impressed we left the apartment and looked at each other and we were just happy! I said I couldn't go home now, I’d like to invite you to dinner, and they said no, that's not possible we are inviting you!" said Dr Koch Gromus.

June 2015

One month after her oral exam, 77 years after her original exams at the Hamburg Medical school, on 11 June 2015, Inge Rapoport was awarded her degree. She said she accepted it in the names of all those who suffered fates worse than hers during the war.

She also said she believed this award was a sign of a new humanitarian spirit in a German university.

Here in her old hometown, they gave her a standing ovation.

Reflection

Meeting Inge Rapoport, with her charisma and charm, and that accent, part German and part 1940’s America, made me feel I was talking with a German Katherine Hepburn – or perhaps also my own grandmother, who died when I was just three.

It was a link to my family past to walk through the capital of a reunited Germany and to be working there.

Visiting the medical school where my grandmother studied left me feeling both churned up and strangely at peace.

I realised that Dr Inge Rapoport was right, and that in some way I couldn't define, there was restitution in seeing the medical school award the degree to her.

She really was doing it for my grandmother ... as well as for all those others, of course, who did not survive the war, and so never had children or grandchildren who could come and walk through the Hamburg medical school campus in the summer and remember them.

Applecake

Inge says she wasn’t much of a cook, so I am including a wonderful recipe from another of our Food is Love grandmothers, for that most German of cakes. Apfelkuchen of course.

I baked it this week in Inge’s honour, just after the radio documentary ran at the end of the Jewish Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur.

Klari’s Applecake

Ingredients

- 3-4 apples - granny smith or golden delicious. If they are large you won’t need 4

- 1 ½ cups plus 1 tablespoon flour (can also substitute the same amount of almond meal)

- ½ cup plus 1 tablespoon sugar

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- ½ teaspoon salt

- 2 eggs

- zest of 1 lemon

- ½ cup butter, melted (can also use ½ cup sunflower or olive oil)

- juice of 1 orange

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- Optional: ½ cup sultanas or raisins, and 1 cup walnuts chopped as topping

Method

1. Peel apples, quarter and slice thinly. Do this first and set aside. Squeeze some lemon juice over them to stop them going brown

2. In a big bowl, mix dry ingredients - flour, sugar, baking powder, salt – and then add eggs, melted butter/oil, orange juice, lemon zest and vanilla. Add apples (and sultanas if using) and stir in.

Note: Klari did the mixing with her hands. You can use a spoon. A mixer is really not necessary!

3. Pour mix evenly into a buttered and floured pan 9” (23 cm) round tin, or 9” x 13” ( 23 x 33 cm) rectangular pan and sprinkle walnuts on top.

4. Bake at 180 for 45 minutes.

5. Let cool. To serve sprinkle sugar on top (optional) or eat with yoghurt or ice cream.

Jerusalem Test Kitchen

This cake was incredibly easy – and very tasty. Very European tasting, which was perfect. It will be even easier if you follow the instructions and don’t what I did which was haul the mixer out and beat the eggs up to double in volume first. In fact DO NOT do this. It gives you the wrong consistency and turns it from a cake to a kind of a pudding. Still v tasty, but not exactly what you want. So do what the recipe says. Use a spoon and all will be well.

It also made a larger cake than I expected – but maybe that’s because I beat the eggs first. I used olive oil – a great choice – and threw in the lemon juice that the apples had been resting in so it came out very lemony, which I really liked. And it made the sultanas even more welcome.

One note re timing. Israeli apples, I know from previous cakes, are slow cooking. So this cake with its large amount of apples took longer than 35 minutes. When I took it out after 50 minutes the apples weren't all done yet. If I were making it again, I might steam the apples for a minute or two first just to get them started.

Verdict: Really, really lovely cake. Even with everything I did wrong, it was delish. Am making it again this week, to see how it goes with almond meal – and a spoon!

Sydney Test Kitchen

Miyuki in Sydney made it with almond meal, coconut oil and rice syrup – and was proud of making a gluten free, dairy free, sugar free apple cake.

But she is going to give it another try, with olive oil instead of coconut oil. She feels, as I do, that coconut oil is a difficult oil to bake with as it has an over dominant taste.

“We found it disturbing,” says Miyuki. "Everything tastes of coconut oil!"

She will also add some tapioca flour because her cake came out with a puddingy consistency. Mine did too, so maybe that’s how it’s meant to be!

Melbourne Test Kitchen

Amanda in Melbourne made it gluten free without too many adaptations. Coconut oil instead of butter; honey instead of sugar and almond meal instead of flower. (Amanda often bakes with coconut oil and isn't disturbed by the taste.) She was out of walnuts, so for sprinkling on top she used macadamias, and then added her favourite, desiccated coconut as well.

It was quick and easy to prepare, and even though she didn't use all the 4 apples she'd sliced, it still took almost an hour to finish baking.

It was too tangy for Amanda’s kids, and as she doesn’t eat apples herself, we're waiting for an adult to come and give us their verdict. So it looks beautiful but no one has tasted it yet!

Inge Rapoport turned 103 this month, and I am having a piece of puddingy, European tasting apple cake with a cup of tea in her honour. As one of her students and life long friends says, “I don’t know any other woman like her.”