AGI ADLER

it’s my sad duty to report that Just Add Love grandmother Agi Adler passed away earlier this year. Her funeral took place on Passover eve, 71 years to the day after she arrived in Australia to start a new life, having survived WW2 and the Holocaust in Hungary.

I have known this sad news since April, but it has taken me all this time to take it in and to publish this tribute, since I last saw Agi in Australia in September 2019. She was then in fine form, her usual warm, breezy, funny self. She appeared on the ABC-TV programme The Drum, an hour long special marking the 80th anniversary of the start of WWII, based around our book Just Add Love.

It remains startling to me that an operation that didn’t go well saw her go downhill so quickly after that.

The Drum, ABC-TV, September 2019. Ellen Fanning, Eddie Jaku, Agi Adler, Eva Grinston, Irris Makler.

Agi is another of the wonderful women that I’ve met through this project, and I count that as my great good fortune.

I’m sending condolences to her family, especially her daughters Joann Adler and Lisa Rosen. Both have been great supporters of Just Add Love, committed to telling the story of their resilient, remarkable mother, letting us take over their kitchens for more than one photo shoot and cooperating with us in such an open-hearted way.

Agi Adler, Joann Adler and Lisa Rosen (COPYRIGHT: David Mane)

Lisa and Jo say that sharing her story with us here at Just Add Love enabled Agi to talk more about her wartime experiences during the last 5 years than she had during the previous 6 decades. Needless to say, it makes us truly happy to be the channel for that, since when you read her story below, her generosity of spirit, and clear-eyed way of seeing the world jump off the page.

I am also including one of her recipes, of course, since her cooking is part of her legacy. It’s part of how she held her new family together, back in the days - not unlike these Covid-19 times - when you cooked a meal from scratch each night.

LIFE STORY

Agi Adler was a great cook, a talented seamstress and a wily card player. She had a sharp wit and was also kind, two qualities not always seen in combination. She was also a much loved wife, mother and grandmother.

Agi with her grand-daughter Sophie Rosen. (Copyright David Mane, 2015)

Agi was born in Budapest, the elegant Hungarian capital, in 1930 but lived most of her long life in Australia.

She arrived in Sydney alone, aged 19, a refugee preparing to make a new life. World War Two had changed everything, robbing Agi of her family – by the end of the War she was an orphan -- as well as an education and the stable happy life she’d known growing up.

LUCK

Yet despite all this, looking back, Agi told me that she believed she was lucky.

“I wasn’t taken to a concentration camp of any kind, nor transported to another country. I wasn’t forced to work, forced to march, forced into a gas chamber, nor did I see others forced to do the same.” said Agi Adler.

Perspective is everything, which is part of the lesson this generation of remarkable women can teach us.

FAMILY

Adolf and Margaret Fenster lived in Budapest, with their 2 children, son Steven and daughter Agi, 7 years his junior. Agi’s grandmother, Margaret Weiss lived with them in their large rented apartment in the centre of town.

Agi's mother Margaret and her father Adolf with her brother Steven around 1926, Budapest.

Agi’s father owned a fabric shop, and her mother stayed home and looked after them all.

“We were 10 minutes walk from the parliament in the 7th district. It was called The Belvoir which means literally the centre of the town. But there was life and shops everywhere. Budapest was spread out, like Paris.”

Budapest famous Chain Bridge, as it looked in the 1930s, when Agi was growing up in the city..

BUDAPEST

Budapest was known then as the Queen of the Danube. A 1930s travelogue gushed that a “gay cosmopolitan crowd of pleasure seeking strangers” were “fast making the city one of the happiest in Europe.” Have a look at the video below, it’s a blast of nostalgia, with images of Hungarians promenading along the Corso, rural women selling embroidery and everyone bathing in the pools of ‘the greatest health resort in the world’.

But there was a darker side to the 1930s too.

Hungary had suffered great losses in World War I, which profoundly affected the generation that grew up between the 2 wars. In 1930s Hungary, a song called Gloomy Sunday (later translated and performed by Billie Holliday) was dubbed The Suicide song and blamed for a spate of people taking their own lives. Things grew so grim that authorities began a campaign to make Hungarians smile again, taping up their faces into the right lines. However the masks didn't solved the problem.

Across the continent, bitterness was incubating into Fascism.

Hungarian woman being trained to smile, 1937. This image captures the trauma of the interwar years, when Fascism was incubating across Europe. Photo: Fotograaf onbekend, collection o Illustrated magazine Het Leven (1906-1941) Images via Memory of the Netherlands

WAR

When World War II began Hungary sided with Germany. After signing a pact with Hitler, Hungary imposed Germany’s anti-Semitic and other racial laws. (Gypsies were also a Nazi target, and Hungary had a large Roma population.)

“From 1939, when the War began, as Jews we were no longer permitted to own a shop. My father had to have a sleeping partner, a non-Jewish man to ‘own’ the shop that he actually owned himself," said Agi. "My brother couldn’t go to high school, he had to finish when he was 14 or 15. Steven was a brilliant student and he would have gone to university had there been a chance."

LABOUR FORCE

In 1940, when Agi was 10 years old, her father was called up for the Labour Force, an alternative to military service for "politically unreliable" men, mostly Jews, who were prohibited from serving in the Army by the newly adopted race laws.

“My father was very short-sighted and they sent him back. So everything is fine, he’s not going,” Agi recalled in her interview for Just Add Love.

After Germany attacked Russia in 1941, Hungary sent most of its Labour Force units into combat in Ukraine. They were brutally treated, with some men even used to clear mine fields, marching through them before the regular troops advanced.

The war was costly for Hungary. Graves of Hungarian soldiers killed fighting for Germany in Ukraine, 1942 (Photo: Don Bend)

In 1942, Agi’s father was called up again. Believing he was going to be sent back home, as he had been the first time, he didn’t take anything with him.

48 hours later he was in Ukraine.

“He sent us a postcard from there. All our names are inscribed on it,” said Agi. “And believe it or not he sent us money from there. He was doing a shift as an orderly in a hospital. But he didn’t return. We don’t know how he died. All we know is that we lost him in January 1943.”

Agi's father Adolf Fenster in the Hungarian Labour Force, 1942. His precise cause of death is unknown, but he didn't return from his service in Ukraine.

SCHOOL

Agi was allowed to continue her studies, unlike other Jewish children across Europe.

“I was allowed to go to school because after my father was declared dead, I was a war orphan and my mother was a war widow. That’s how they designated us.”

“My father being sent to the Labour Force when I was 12, that was the first thing I really noticed. Until then, I didn’t really feel the War personally. Not until the last week of the War did I ever go hungry. It only became extreme when the Germans entered Hungary.”

Hungarian losses mounted, but some Nazis still viewed it as 'a land of nightclubs and white bread, where the privileged could live without rationing or conscription.' Hungarians didn’t see things that way and began conducting armistice talks with the West. Hitler, enraged by this treachery, attacked Hungary In March 1944.

Agi and her mother watched it happen.

Hitler meets with Hungarian Regent Admiral Horthy, 2 days after Germany occupied Hungary, Match 1944 (Photo: Getty Images)

GERMAN TANKS

“My mother and I were on the way to a cinema, at the far end of Budapest, opposite the western railway station. It was Sunday lunchtime, 19 March 1944, and we were stopped at the big boulevard because German tanks were rolling in. Nobody knew about it. We stood there not believing what we were seeing, just the two of us, my mother and I. It was amazing,” Agi recalled.

The Jews of Hungary now learned the terrible difference between being ruled by an ally of the Nazis, and the Nazis themselves.

JEWS

On 5th April, 1944 Jews began to wear the yellow star, but Agi still went to school.

“Towards the end of the year - our end of year was June - one teacher marked us by asking ‘Are you Jewish?’ If you said yes, he instantly gave you 5 on a scale of 1 - 5. The lowest mark possible. I can actually show you my report cards, I have them,” said Agi.

That was the end of Agi’s schooling. Meanwhile, her family received another blow. On 17 April 44, Agi’s brother Steven, then 20 years old, was called up to the Labour Force.

"And that’s another sad story because he was then marched from one end of the country to the other. He finished up in a little town close to the Austrian border. We could correspond, we could send each other cards. And I’ve still got all the cards from him, but I can’t look at them. It’s too painful.”

ADOLF EICHMANN

When German troops entered Hungary, so too did the SS, and its Captain Adolf Eichmann, a bureaucrat who had organised the murder of Jews across Europe.

By that time, in the spring of 1944, the Nazis had succeeded in exterminating most of the continent’s Jews. First had been the large Jewish communities in the East, in Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic states and other countries bordering Russia where people had been shot and buried in pits where they lived.

Next, the Jews of Western European countries occupied by the Nazis eg Holland, Belgium, Greece, Jugoslavia, and of course Germany itself, were transported to concentration camps and killed there in gas chambers, a new ‘industrial style’ method of murder.

But Hungary’s Jewish communities remained largely intact.

SPEED

By July 1944, only 4 months after Agi and her mother saw German tanks roll into Budapest, Hungarian and German troops would deport nearly 440,000 Jews to death camps in Poland.

Approximately 320,000 were killed upon arrival and the rest worked as slave labourers in Auschwitz and other camps.

Hungarian Jews arriving at Auschwitz, May 1945. These women and children were separated from the men and working age women without children, so they could be killed immediately. (Photo: Yad Vashem, ‘The Auschwitz album.’)

The stories of grandmothers we have featured in this project, Baba Schwartz, Tooby Lerner and Eva Grinston, describe the terrible fate of Jews in rural Hungary, and other areas under Hungarian control such as Romania and parts of Slovakia.

BUDAPEST

But things were different for the Jews in the Hungarian capital, including Agi and her mother and grandmother. Under pressure from Allied governments, the Vatican and the Red Cross, in the summer of 1944 Hungarian Leader Admiral Horthy halted the deportation of Jews from Budapest to the death camps.

Some 200,000 Jews remained in Budapest, alive, yes, but living increasingly bitter lives. They were forced into a ghetto. Agi didn't have to move, as the ghetto came to her. The apartment block where she lived became a residence solely for Jews. Christians were moved out and Jews brought in from elsewhere.

“My grandmother’s sister, her two daughters and their families came to stay with us. So there were eleven of us in the one apartment -- my grandmother, her sister, her brother-in-law, their two daughters and their children.”

Jewish women being rounded up in Budapest, 1944. (Photo: Bundesarchiv)

FIRST HIGH HEELS

Jews could still enter and leave, so their lives changed, but they also went on, as Agi put it.

“I turned 14 in August. I was a little girl who got her first high heeled shoes which was a wedgie with cork. Well to me that was the heights of, I can’t even tell you the words. I was in another world when I got that shoe with an ankle strap on my skinny little legs. My god what I must have looked like!" Agi said.

“In September, the war intensified in our area as well. It was Germans and Hungarians vs Russians. There were almost nightly air raids and we had to go down to the cellar, although I didn’t much, to my grandmother and mother’s horror. I was not a very good little girl. I didn’t really listen much.”

SUPERSTITIOUS

In addition to the extended family, more people were moved into Agi’s apartment, including the parents of a friend of her brother Steven. Agi’s mother Margaret was very friendly with that mother. They were both superstitious and dealt with the tension and fear of life during wartime by doing something unexpected. They played the Ouija board.

You ask and the Ouija Board answers... Agi's mother and her friend turned to superstition to deal with the uncertainty of the time. (Photo: Jon Santa Cruz, Rex Features.)

“They were both playing the Ouija board and believing in the bloody Ouija board. The Ouija board said: You will be alright. Can you believe that?” asked Agi. “Well they did. So we didn’t get any special passes or anything that we could use if we got into trouble… like the Schutz-pass.”

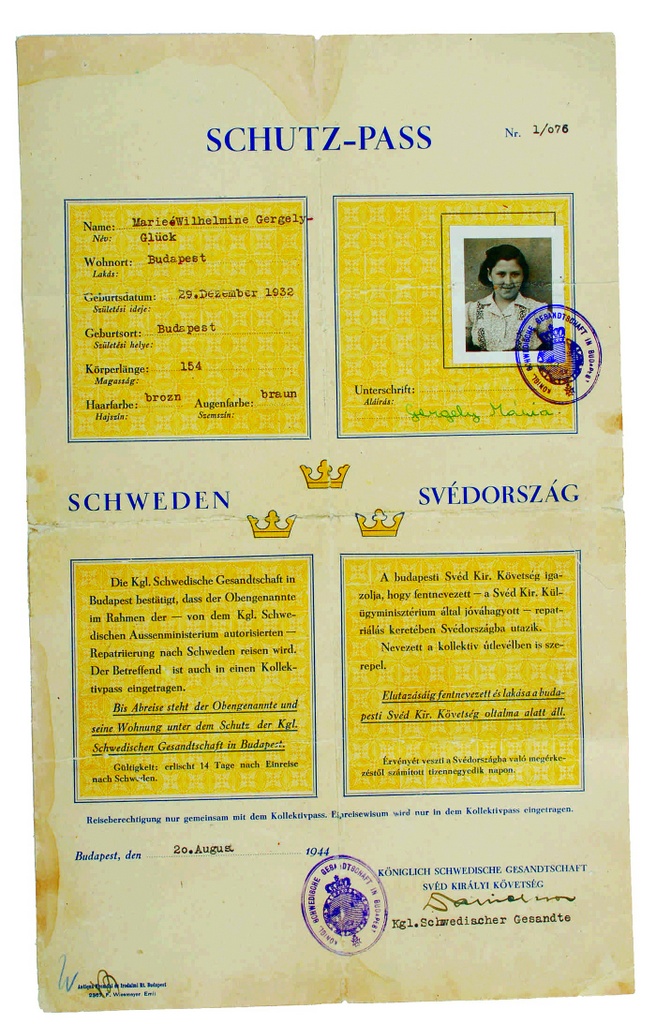

SCHUTZ-PASS

The passes came from Swedish architect-turned-diplomat Raoul Wallenberg. Tall, multi-lingual, and brave, he was 31 years old when he arrived in Budapest in July 1944 on a mission to save Jews. In the summer of that year, 2 men were circling the Jews of Budapest - Nazi Eichmann, trying to muder them and Swedish Wallenberg, trying to protect them. It was a fight between good and evil and you can read more of Wallenberg’s amazing story here and here.

Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg. Passport photo, around 1943.

With American funds and Swedish diplomatic immunity, one of the first things Wallenberg did was to create a fake document which would confer ‘diplomatic immunity’ on the holder to prevent them being picked up by the Nazis.

He created a colorful, imposing, official-looking document, and gave it a German sounding name.

Schutz-Pass from August 1944, issued to a Budapest girl younger than Agi. Agi's mother didn't try to get this protective pass till it was too late.

He employed 400 Jews to make these passes around the clock, including a woman called Agnes Adachi.

"He made a game out of outfoxing the Nazis, but he played it with the utmost seriousness. Most of all, he was like a big brother one looked up to, and he had the most beautiful eyes that I have ever seen. They were so beautiful and they saw everything," said Agnes Adachi.

Wallenberg's next step was to create safe houses for Jews.

He purchased thirty buildings and flew Swedish flags above them, next to the Jewish Star. The buildings were given Swedish government protection and Wallenberg set up hospitals, schools, soup kitchens, and a special shelter for 8,000 children whose parents had already been deported or killed.

Wallenberg's Schutz-passes are credited with saving some 20,000 Jewish lives. But Agi’s mother didn’t have one.

“We could have got a Schutz-pass back then, in July or August. Well for money you can get everything. But my mother said, ‘No I don’t want it, we’ll be alright’. That’s what the Ouija Board told her,” Agi sighed.

ARROW-CROSS

By October 1944, things were going downhill fast.

Arrow-Cross, Hungarian Fascists, take power in Hungary with Nazi help in October 1944

Despite the presence of German troops in Hungary, its leader Admiral Horthy re-opened negotiations with the Allies.

In October, while he was actually signing the armistice deal with Russia, the Nazis kidnapped Horthy’s son, took him to a concentration camp, and deposed Horthy himself before the armistice could take effect.

The Nazis then assisted Hungarian Fascists called the Arrow-Cross to take power.

German tank and troops in Budapest, October 1944. (Copyright: Bundesarchiv)

Agi clearly remembered the day of the Arrow-Cross takeover, 15 October 1944.

“That was also a Sunday. We weren’t allowed to go out for the next six days. We were literally locked in. The first night a militia made up of 15 year olds with rifles were herding 30 or 40 Jewish children down the street right under our windows. We had wooden shutters on the inside, and we looked through the cracks and I saw the small Jewish children being taken away. That night I decided that the Arrow-Cross were just the worst.”

She shared another memory from that night.

“Later they came and rang the bell and everybody had to go to the courtyard. Every house had a courtyard and a bell, which they rang to warn us when the military bombers were coming. And the people on the right they were taken. The people on the left they were taken. And we were sitting up all night waiting and nobody came for us," she recalled.

"Our whole building was taken except us and our next door neighbour. He was an old gentleman who ran a business from his apartment, and he said he’d paid off the police,” Agi said, describing how she and her family were locked in for the next 5 days.

“If you didn’t have food in the house it was too bad. And the first time I think it was Saturday afternoon for a couple of hours we were allowed out. And from then on life became pretty messy because they were in power and they were unbelievable,” she said.

Arrow-Cross militias arrest Jews in Budapest, October 1944. The Jews were deported to the death camp of Auschwitz, or shot in the city itself. Almost 80,000 Jews were murdered in Budapest in the space of 3 months before Russian troops forced the Nazis to retreat in January 1945. (Photo: Bundesarchiv)

DEPORTATIONS

The Arrow-Cross resumed the deportations of Budapest ‘s Jews to the death camps, and also began mass executions, rounding up Jews in the capital and shooting them.

Many were taken to the banks of the Danube river, where they were tied up and then every third person was shot, falling into the river and dragging the others down to drown in the freezing water. This was done to save bullets. The victims were also forced to remove their shoes before they were executed, apparently because shoes were also valuable.

This is a monument to the thousands of Jews killed here on the shores of the Danube, in Budapest in late 1944. They were forced to remove their shoes before being tied together and shot. (Photo: Adelina Wong)

Raoul Wallenberg – whom Eichmann called the ‘Jewdog Wallenberg’ – tried to intervene here too. A woman from his office recalls once when Wallenberg heard that Arrow-Cross militias were shooting women and children at the river, he asked his staff who could swim.

“We went — it was a cold night— and jumped into the Danube. The water was icy cold.”

They saved around fifty people.

MARCHES

By late 1944, Soviet troops had cut the rail lines to Auschwitz, but this didn’t stop the deportations. The Jews were simply marched out of Budapest on foot. They walked 200 kilometres to the border with Austria. Those who didn’t die along the way were taken to work as slave labourers.

On the 8th of November 1944, Adolph Eichmann ordered a general roundup of Jewish women and children. Women in high heels, caught in the street, children and the elderly took a week to walk to the Austrian border. They had no food or winter clothing. The dead and the dying were left by the side of the road.

We know this because Raoul Wallenberg and another Swedish diplomat drove along the route of the march, giving out food, clothing, fresh water and Schutz-passes where they could. On the first day, they rescued about 100 people with these passes.

Photograph taken from Raoul Wallenberg's car, 1944. These Jewish people had been marched out of Budapest by the Arrow-Cross, but were now were returning home, after Wallenberg intervened to help them.

In the days that followed, Wallenberg made repeated trips along the route and continued his rescue efforts at the border, organising Red Cross trucks to deliver food.

He rescued about 1,500 people in this way.

Towards the end of November, Eichmann received orders to return to Berlin and to halt the marches and all ‘liquidation operations’. In light of Germany’s crushing military losses, Heinrich Himmler was sending out feelers to the Allies about negotiations.

AGI’S MOTHER

There was one last round-up before the marches were halted.

It took place on 13 November 1944.

The Arrow-Cross came to Agi’s apartment building and rang the bell. All the inhabitants of the apartment, including Agi and her mother Margaret, went downstairs.

Agi’s mother was then 42 years old and the cut off for women to be taken, ostensibly for work, was age 40.

“You had to present yourself between the ages of 16 and 40. I was 14 and my mother was 42, so we thought we were alright,” said Agi.

But that morning the Arrow-Cross took all the women, including Agi’s mother. Agi wanted to go with her, but a Hungarian officer told her to stay behind.

“He said no, your mother is a war widow, she’s going to be sent back from the first checkpoint. And you’re too young anyway. I was 14, but I looked even younger. So I stayed behind. And she went.”

Agi paused for a moment before resuming.

“But that day nobody was sent home. Whoever was taken on the 13th, and I spoke to a lot of people back then and after the war, nobody came back. I don’t know why. I was 14, alone at home with my grandmother. And my mother wasn’t coming back. My childhood was actually happy right up till that day in 1944 when I lost my mother.”

It seemed so capricious. Why take Agi’s mother but leave Agi behind?

“I was too young. From the country areas, they took all the Jews, including children. From Budapest, they didn’t. Why not? You figure it out. I don’t know.”

SCHUTZ-PASS

Agi's mother and the other women were marched to the Austrian border.

“We did get a letter from there. My mother asked to please make a Schutz-pass for her, although by then it was really too late,” Agi said. “Believe it or not I got a forged one. I spent an arm and a leg on it and tried to send it to her there, but it didn’t reach her.”

“When I think about it it’s so stupid. The Ouija board - can you believe that? – told my mother that she would be alright. And she and her friend who listened to that Board, they actually went away together and never came back together.”

GHETTO CLOSED IN

“It was at this time, towards the end of November, that the Germans started building the ghetto walls, closing us in,” Agi recalled.

There were now fewer than half the Jews left alive in Budapest - less than 100,000 left of an original population of 200,000. They were sealed into the Ghetto, Agi and her grandmother amongst them, on 20 December 1944.

“Bear in mind they were well and truly losing the war by this stage. There were Hungarians at the end of our street, waiting for the Russians to arrive. The end of the street, not as far as Bondi Road is from this apartment. The Nazis spent money, manpower, everything just to get rid of us. That was their main aim, although the Russians were literally on our doorstep,” said Agi.

No food was allowed into the Ghetto, leading to widespread starvation. No waste was collected and the dead lay piled in the streets. Diseases spread, leading to further deaths.

FINAL DAYS

At the border, Agi’s mother was put on a river barge, apparently headed for Austria. There the trail goes cold. No one knows precisely what happened to the women sent by river that day.

Agi put a lot of effort into searching, but never met anybody taken away that day who survived. The fact her that her mother was taken on the last transport of Jews from Budapest tormented Agi all her life. Looking devastated during our interview, she suggested it was destiny.

“It has to be. My mother was a good person, so why should she be taken on the final transport from Budapest and killed?” asked Agi, with tears in her eyes.

MASSACRE

In early January 1945 Raoul Wallenberg learned of a plan, masterminded by Adolf Eichmann before he left Hungary, to massacre all the Jews remaining in the Budapest ghetto.

The killing was to be carried by a task force of officers from the SS and the Arrow-Cross, and it was to be done quickly, before the Russian army could take Budapest. The German commander in Budapest, General August Schmidthuber, was prepared to carry out these orders, even though Russian troops were by now on the outskirts of the city.

Soviet soldiers manning anti-aircraft guns as they fight their way through Budapest, January 1945. (Photo, Russian WW2 archive)

Wallenberg sent word to the German General, via an Arrow-Cross contact, telling him that if the planned massacre took place, Wallenberg would ensure that the General would be held personally responsible and would be hanged as a war criminal.

The General reconsidered.

He gave orders that Ghetto ‘Aktion’ should not take place.

Wallenberg saved literally tens of thousands of lives. But it was to be his last victory.

LIBERATION

By mid January 1945 there was street fighting around Agi’s apartment.

“If you were awake during the fighting, you went down to the cellar, because a stray bullet could get you. When we checked our beds, we found bullets in them.”

On 18 January 1944, German troops retreated.

Victorious Soviet soldiers marching through Budapest after forcing the German soldiers to retreat, January 1945.

Russian troops tore down the walls of the Jewish ghetto. They found 70,000 Jewish men women and children alive there – including Agi and her grandmother.

“We were only in the ghetto for four weeks, no 29 days to be exact. 11 days in December – they closed us in on the 20th -- and 18 days in January before the Germans retreated. Building that Ghetto was one of the Nazis’ last acts in Hungary,” said Agi.

In addition, another 25,000 people were alive in the Swedish safe houses, and 25,000 people of Jewish origin were hiding in Christian homes, monasteries, convents and churches.

In all, 120,000 of Budapest’s Jews survived. It was the only substantial Jewish community left in Europe.

It’s estimated that 100,000 of these people owed their lives directly to Raoul Wallenberg.

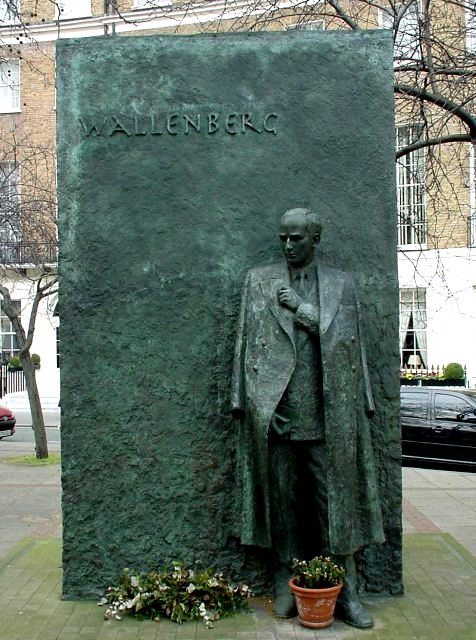

WALLENBERG

The arrival of the Soviets was to prove terrible for Wallenberg personally. Accompanying the troops were the Soviet secret police, the NKVD. They arrested Wallenberg on suspicion of being an American spy.

He was last seen with Soviet officials in mid-January 1945. After that he disappears.

For years, Moscow denied knowing anything about his whereabouts. Decades later officials suggested he died in a Soviet prison in 1947, but provided no actual evidence. There were reported sightings of him in the Gulag up to 10 years later.

Even now, after seven decades, the best we can say is that the exact date and circumstances of Wallenberg’s death remain uncertain.

It’s one of the saddest stories of World War Two.

A man who volunteered to go into Budapest in order to save Jewish lives, and did just that, saving tens of thousands of people, who survived all his dealings with the Nazis, was then taken prisoner and murdered by the Russians.

It’s no fate for a hero.

Raoul Wallenberg 1913 - ?

RECOGNITION

Many of the Budapest Jews saved by Raoul Wallenberg migrated to Australia after the war. There is a monument to him in Sydney, put up by the grateful people whose lives he saved. It joins monuments all over the world – Stockholm, Budapest, Tel Aviv, London, Buenos Aires.

On the centenary of his birth, in 2013, Wallenberg was declared an honourary Australian citizen. Prime Minster Julia Gillard said it was the first time that Australia had bestowed such an honour, calling it a “symbolic recognition of Mr Wallenberg’s tireless devotion to human life during the Holocaust.”

“The lives of those he rescued are Mr Wallenberg’s greatest memorial and Australia is honoured to have survivors he rescued living here today,” said Prime Minister Gillard.

LOOTING

“The minute we were liberated and the door was opened I was on the street. It wasn’t just the exhilaration of freedom. We needed food!” said Agi.

"We went zombrovnie, which means looting. I lived not far from a department store, like David Jones but not quite as big. And I remember exactly what I got. I took a box of about 50 fountain pens. I don’t know why. I also got a pair of shoes for the little boy in our apartment because he had no shoes,” Agi said.

There was a lot of damage in Budapest after the War. The famous Chain Bridge, linking the 2 sides of the city, was destroyed in fighting (Photo: 1945)

WINTER

“Luckily, it was a very cold winter because corpses were stored in the corner shop on the street where we lived. They were stacked up like wood, practically to the roof. We had them lying in our courtyard for 2 weeks. But the snow was high, and they stayed frozen until officials finally came with a big sleigh and loaded the bodies on and took them away for burial somewhere,” says Agi.

SLEIGH

“Some girls came back to their apartments in our building and found they were empty. So what do they do? They go out looking for furniture. And I go with them. But we can’t carry the furniture we find, can we? So when the workers go in to the courtyard to get the next lot of bodies, there's this beautiful sleigh which we take!" Agi said. "And we went from place to place. We got furniture to fill their empty apartment and then we took the sleigh back,” Agi recalled, marvelling at her own behaviour.

“And that’s why I feel so bad for my grandmother, now when I’m a grandmother. What she must have gone through with me, I can’t believe it. I really cannot believe it,” Agi said.

BROTHER

Agi understood that her parents would never return, but she still hoped to see her brother Steven. Then 3 months after Budapest was liberated, she learned his fate.

On 25th April, 1945 a cousin returned from the concentration camp of Mauthausen, where he had been held with Steven.

“My brother had typhoid and somehow survived that. But when the Nazis cleared the camp before the Americans came, they took prisoners out on a death march. Steven wasn’t in any condition to walk, and I don’t think he ever arrived at the destination,” said Agi.

“But we had already been liberated by then for 3 months, from the 18th of January, that’s 3 months and 1 week. Can you imagine that? He died after liberation. That’s what is so sad,” said Agi.

Below: Left, Agi's brother Steven, who did not survive the War; Right, Agi aged 14, when she was in the Budapest ghetto.

Agi tried not to torment herself with these near misses. Her mother taken on the last transport of Jews from Budapest. Her brother dying on the Death March from Mauthausen, after Budapest had been liberated. To do that, she reminded herself of the reality of war.

“You know, after we were liberated on 18 January, a woman in my building went back to her original apartment on the other side of Budapest to check whether it was still standing. But the war was still going on there, on the other side of the river and she was shot and died.”

Life is cheap during wartime. Survival is often dumb luck.

SMUGGLING

Agi didn’t go back to school. There was no one to make her do it.

She worked within the chaos, trading on the black market. Cigarettes. Money. Whatever people needed.

“My friends were all young. We were most of us in very similar circumstances. We would ride illegally on the trains, bringing back eggs or butter, or whatever we’d found which we could trade.”

“A couple of boys that established a cigarette factory in the countryside, and decided I was the right person to be the overseer. So I became the overseer with privileges to smoke as much as I wanted to. I was 15 years old,” said Agi.

GRANDMOTHER

“In May 1945, I was out there in Romania on the cigarettes, when I suddenly got message I had to go back home because my grandmother was in hospital. Now when we went to Romania to sell our cigarettes there were no borders, we had no passport. I travelled with 3 others, for 5 days on a flat top railway carriage. But how to come back to Budapest because now suddenly there is a border and I have no papers? Anyway I managed to get back,” Agi recalled.

“I went to the hospital. My grandmother had had a stroke. She didn’t know me any more and she passed away. She was 66 years old,” she said.

Agi's grandmother Margaret Weiss survived World War Two in Budapest, but died soon after of a stroke, in May 1945. She was 66 years old.

ALONE

Fourteen months after Agi and her mother saw German tanks roll into Budapest, 1 month after the end of the War in Europe, Agi was now alone with no close family at all. The only source of stability was the family apartment, where she’d lived all her life.

“I never moved. That was the only luck in my whole life. I was never displaced, so to speak.”

Still, she was a wild thing and no one stepped in to help.

“I had two aunties, but they weren’t interested in me. The Red Cross found me and every year on my birthday I went to the warehouse where they stored clothes which Americans had sent. They let me choose what I wanted. It was a birthday parcel. And that was the clothes that I had,” Agi recalled.

She reflected on why she didn’t spin off the rails.

“Once years later in Australia, I saw a psychologist and I actually put it to her. Tell me why didn’t I go down another path? Why didn’t I become a prostitute? I needed food. She said, ‘Because your beginning was a happy stable environment and that’s why you stayed on the straight and narrow.’”

MIGRATION

In 1946, a Jewish committee offered to relocate war orphans like Agi to Canada.

“It took 2 years to organise. After I’d said yes to Canada, I didn’t hear from them for months. Then on the 8th of October 1948 I received a postcard: You are leaving on this Sunday at 3.00pm. Be at the railway station, to catch the Paris train.”

“I bought an overcoat from my mother’s cousin who made me pay for it, charming gentleman. A wicked aunt took most of my mother’s possessions, including clothes, money and jewellery, and in return she gave me $20 and a jar of goose liver in goose fat which I took with me,” said Agi.

That was all that Agi had with her when she turned up at the railway station with 8 other Jewish orphans on Kol Nidre night, the night before Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement.

They arrived in Paris on 12 October 1948.

“One of the women on the organising committee asked us, 'Who is over 18?' There were three of us, including me. And she said, ‘Well you can get back on the train and go home.’ So we looked at her. Are you out of your mind? We couldn’t go back, we didn't have a visa for that!” Agi recalled.

They managed to persuade her they had to stay, but Canada was now out of the question, as it only issued visas for orphans under 18. When the Welfare Committee suggested Australia, Agi said yes.

A COAT AND GOOSEFAT

It took 6 months before passage on a boat to Australia came through. Agi lived in a French chateau with the other war orphans.

“I shared the jar of goose liver with everybody. We used to have midnight suppers because that was everybody’s favourite.”

“I still love goose fat and I eat it on this Riga type bread. I love it with just some salt, that’s it; I could live on that."

19 year old Agi Fenster in the front row, aboard the Cyrenia, on her way to Australia. April 1949. (Photo: personal collection)

AUSTRALIA

Agi sailed into Melbourne Port aboard an old passenger ship, the Cyrenia, on 8 April 1949, and caught the train up to Sydney the same day. It had been snowing when they left Marseilles, the first spring snow there in 50 years, but when they reached Sydney, where it was officially autumn, Agi remembered it being warm and sunny.

“It was unbelievable weather. We were still going to the beach in April. The Jewish community welcomed us, we were taken to a Sunday lunch in a beautiful home and I thought, this is a new life.”

Photo: David Mane

Agi found work in a clothing factory in Elizabeth street in downtown Sydney. “Once they realised how little I knew, instead of firing me, they trained me up,” she said, laughing.

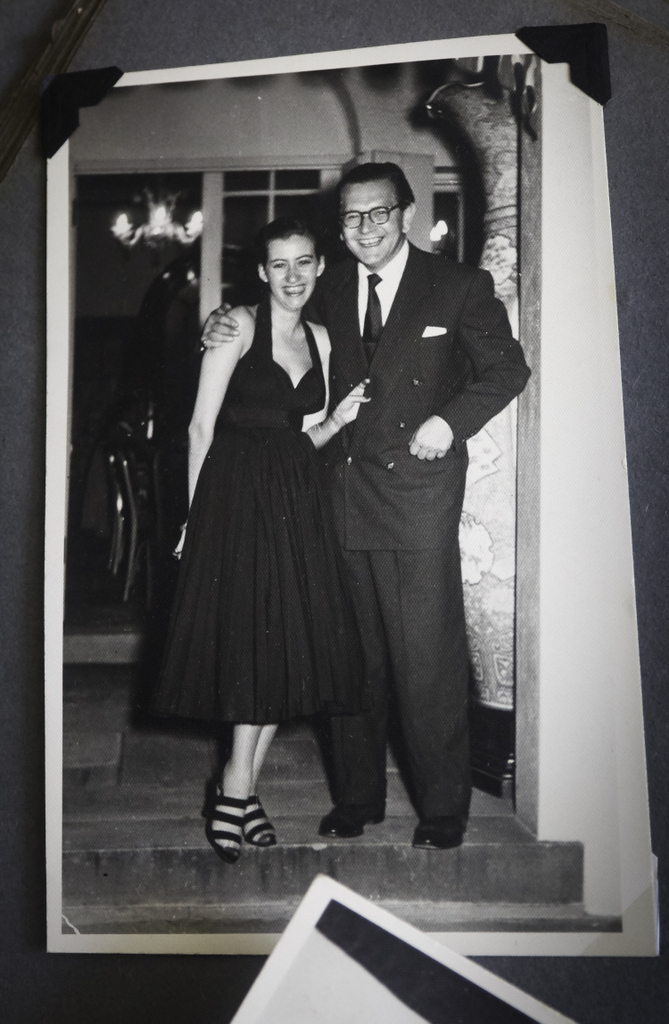

AND THAT’S HOW I MET YOUR GRANDFATHER

Also working at the factory was Bob Adler, a German Jewish migrant who had spent the war in Sydney with his sister.

“So in that respect he was lucky. He was also handsome and was always stylishly dressed and that reminded me of my father,” says Agi.

Agi and Bob Adler, 1951 (photo: personal collection)

“He had lots of girlfriends and I worked there for 18 months before we got together. We were married in 1952 and had 59 happy years together. We were very compatible. He was a good man, a good provider, and a good husband and father to our 2 daughters, Joann and Lisa,” said Agi.

"You know he was well-dressed right to the end, even when he had cancer and was going to the oncologist."

COOKING

When Agi got married she didn’t know how to cook. But remembering the tastes of her mother’s kitchen, she went to the library and borrowed Hungarian cookbooks. She also exchanged recipes with other migrant women and slowly recreated the tastes of her Budapest childhood. These are the dishes she cooked for her children and grandchildren in Sydney to the end of her life.

“And my grandchildren are the light of my life,” she smiled.

Agi looks through the old photos with her grandsons, Harrison and Richard Rosen. (Photo: David Mane)

POTATO BAKE

This dish is known in Hungarian as Rakott Krumpli. The original recipe had 8 eggs, but it works better when the eggs don’t dominate, so we've decreased them to 4. You can go back to 8 eggs, or you can add finely sliced onions, or some good salami or sausage if you're that way inclined. Or you can keep it simple. All options are good!

Photo: David Mane

Rakott Krumpli – Agi’s Potato Bake

SERVES 6

INGREDIENTS

1 kilo kipfel or desiree potatoes; you want the least ‘crumbly’ potato

4 eggs

600 mls sweet cream or: 350 mls sweet cream mixed with 250 g sour cream

salt and pepper

Optional: one onion, sliced thinly

Optional: non-vegetarian, non-kosher version, which everyone says is much tastier – 200g Hungarian sausage, sliced up

Photo: David Mane

METHOD

Peel and boil potatoes in salted water for about 15 mins till par boiled. You want them firm enough to slice. Leave to cool and slice thinly

Boil eggs, these do have to be fully boiled! Leave to cool, slice with egg slicer

Slice onion thinly, if using.

Mix creams together, adding salt and pepper to taste

Now you layer. It's a good idea to put a little of the cream on the bottom of the baking dish, so it doesn't stick. Start with potato, then a layer of eggs - and onion or sausage if using – making sure you end with potato.

Pour cream mix over the layered potatoes and eggs and bake in a moderate oven till the top is brown - around 30 minutes.

Photo: David Mane

FEEDBACK: I don’t usually cook vegetables in cream like this, but I can see why it’s popular. and not just in Hungary - Pomme Dauphinoise anyone?

I have learnt one thing. An egg slicer – which I don’t have – really will provide you with a smoother result. Or wait until the eggs are fully cooled. If you don't your eggs can be a bit rough looking, more chopped up than sliced!

There's a reason Agi uses an egg slicer! Grandmothers always know best... (Photo: David Mane)

REFLECTIONS

When we spoke, Agi did not pat herself on the back for her survival, or the life she’d built.

“You’ve got to get on with it. If you don’t you might as well pull up the doona and just disappear.”

In other words, if you don’t make a go of it, you might as well have perished with everyone else, I asked.

“Well I wished that a lot of times. If I showed you my diary from 1944 and 45 …” Agi trailed off, adding that she did find things more difficult as she aged.

“We had our various, I can’t call it hardships, because compared to somebody that was in the Warsaw ghetto, it wasn’t hard. We lived in our own apartment, we lived our life, whatever life it was but we still lived it. I had a very good friend who died three months ago and she spent three years in a Japanese POW camp. I didn’t have to do anything like that,” Agi said.

Her life though, if you don’t compare it to these extremes, was certainly hard enough.

“I don’t know what to compare it with. I mean it was life, we just lived it as it was. There was no choice. You curled up and died or you lived that life and that was it. But the memories get harder as you get older. When I was 15 anything was an adventure. Now it weighs on me.”

Rest easily, dear Agi. You are much missed.

Agi Adler, 1930 - 2020

Agi Adler (Photo: David Mane)