One year ago - what to do with the chicken from the soup

We’re returning to our historical stories this week with Melbourne grandmother Judy Kolt. Lovely, lively Judy is a gardener, a painter, an adventurous cook, and an accomplished pickle and jam maker, as well as the heart of a large loving family.

“My kids say I’m a great cook but then everyone’s kids say their mother is a great cook,” Judy smiles.

She's famous for her Thursday night mezze table, and we’re making two dishes from that table this week. A hearty and delicious curried lentil soup, since it's winter in Australia, and this is a soup for perfect winter, plus a quick and easy Mediterranean Baked fish, perfect any time of year! We will come back and make more of Judy’s dishes in future too.

MEMORY

Judy was a small child in Poland during World War Two, and hers is a story about the kindness of strangers, heroic strangers, actually, and also about recovered memories.

Judy returned to Poland for the first time 40 years after the War, as she was experiencing increased anxiety and nightmares – “they seem to get worse the older you get” - and her husband Hymie thought confronting her past might help her.

He was right.

It was the start of a number of visits over a span of 2 decades, where Judy met people who confirmed her memories – especially the Nuns who saved her – and helped to bring her some peace.

Judy Kolt in her garden with her grand-daughter Aviva Green

Her memoir, Tell it to the Squrrels, is beautifully written and observed, and very moving. It’s told from a child’s perspective, simple and straightforward, without self-pity; like Judy herself, it’s a book full of light and love, matter of fact when dealing with great sorrow.

One of the things the book highlights was how active the Nuns who took in Jewish children had to be. It wasn’t one great act of courage and they were done. German soldiers were constantly entering the convent to search for these children, and each time the nuns had to hide them, or rush them to the clinic, where they covered their faces with bandages to hide their 'Jewish features'.

Since the punishment for hiding Jewish children was death, these women required intense commitment as well as nerves of steel.

ENERGY

Like many of the grandmothers in this project, Judy is full of energy; constantly laughing and doing - the garden, the markets, her art work - as well as seeing her children and grand-children. If you didn’t know about her past, you’d never detect it meeting her. She describes herself as an ‘old chook’ now, still battling the anxiety that her childhood experiences instilled in her, but insists that ageing does not mean giving up!

“You don’t wait for something fantastic to happen in order to enjoy the day. You wake up. If you’re hurting you know you’re alive so that’s alright. I always go out first thing in the morning, and take a little walk around my husband’s garden. And you see a flower opening up. There’s joy in seeing flowers, there’s joy in everything. You don’t have to wait for something special to happen to enjoy life.”

FAMILY

Judy was born in 1936, the daughter of Stefan and Fela Jablonski. Her family owned timber mils in the countryside near Warsaw.

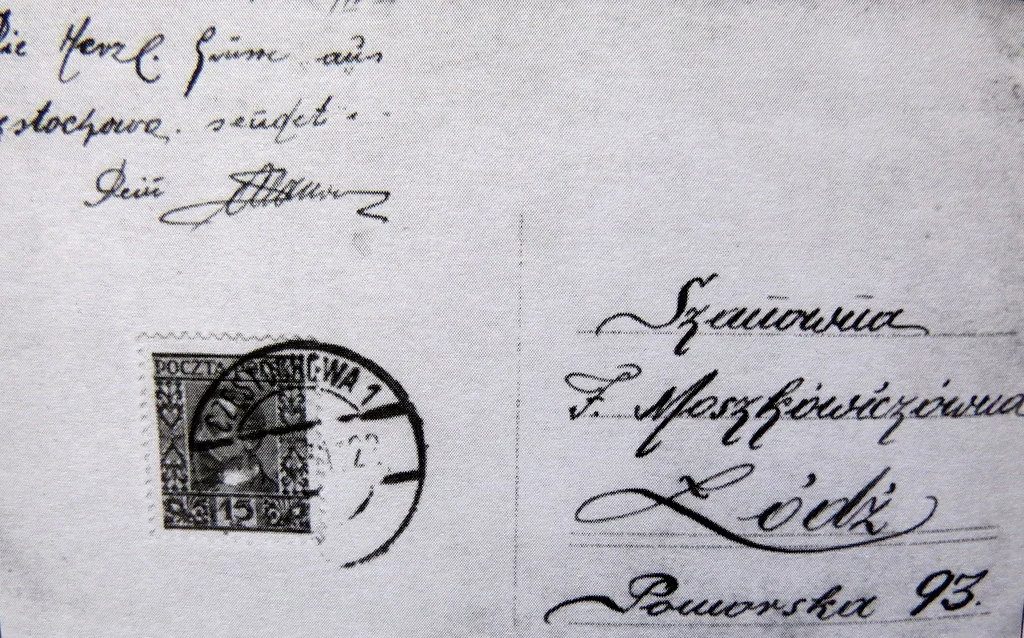

When he was courting her mother, her dashing father Stefan sent her this postcard of him flying a plane. Who could resist that?

Below: postcard, front and back

Judy's older sister Tosia had been born in 1933, the year Hitler began taking power in Germany. 1933 and 1936 were not auspicious dates for Jewish children being born in Europe, but Judy describes a happy family life before World War Two.

“It was a very comfortable and rich family life. There were cousins and aunts around constantly. My parents had a wonderful relationship while I was little. You can’t hide that from children. There were always smiles all around.”

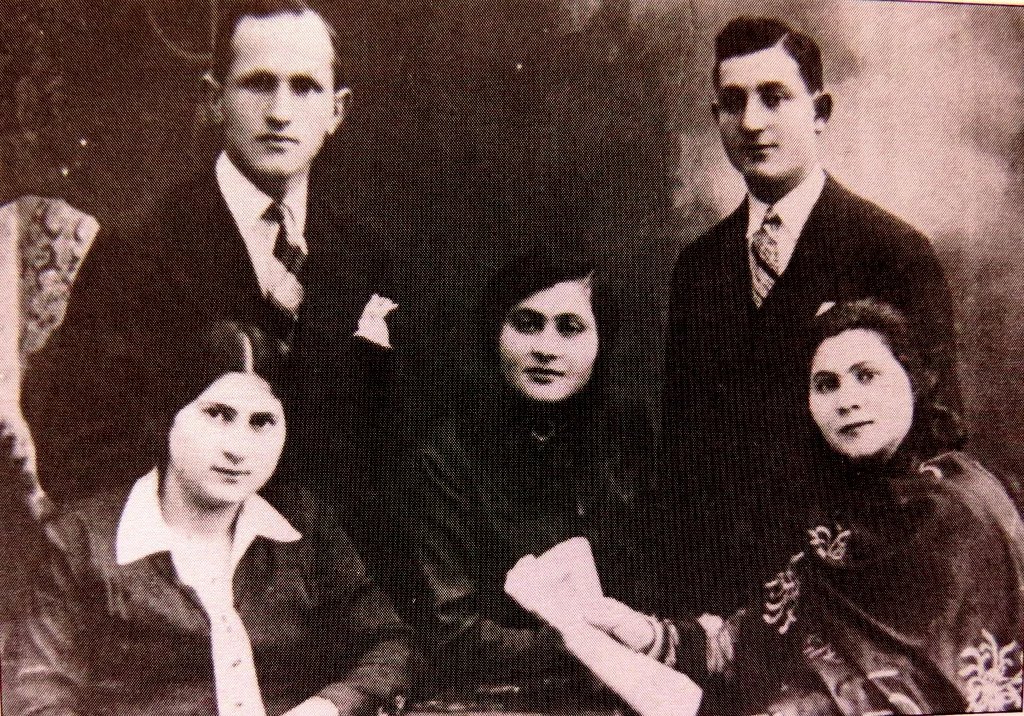

Judy's mother Fela Jablonski, front left with Judy's father Stefan behind her; Judy's aunt Ewa, her husband Natan and his sister Regina. Poland, 1930's. Only one of these 5 would survive World War Two.

1940

The War began when Judy was just 3 years old. Her family went to Warsaw, hoping that they would “get lost” in a big city, but the German bureaucracy was more organised than they expected. They were held in the Warsaw ghetto, until her father managed to have them transferred to Otwock, (pronounced Otvosk) a more open ghetto in a spa town thirty minutes from Warsaw.

Her father hoped it would be easier for them to escape from there.

Otwock railway station, 1930's. It still looks the same today - minus the period cars, of course.

Judy remembers visiting Zofiokwa, a famous psychiatric hospital, originally run by Jewish doctors from Switzerland.

“I didn’t find out until much later when I was grown up that the reason Mum took us there was because there were a lot of Jews hiding there while they were trying to find ways out. Eventually it was liquidated. We actually saw that, all the patients being shot. And the two doctors were taken as well. They didn’t survive.”

Below: German nurses at the Zofiokwa hospital during WW2; the building, standing empty today

FATHER

Judy lived in Otwock with her mother, sister and other relatives, while her father Stefan lived outside on Aryan papers ie passing as a Polish Christian, working his business connections to find safe places for as many members of his family as possible.

He soon connected with the Underground, trading in information and weapons as he moved about trying to keep his family alive.

On Judy’s 4th birthday in September 1940, he came to celebrate with her and took her for a walk in the forest, which bordered the Otwock ghetto.

“He said to me, ‘Now you are grown up, you are four years old, you are no longer a child. Soon I will have you out of here but you must remember always to look people straight in the eye so they won’t know that you are frightened. Don’t ever forget who you are but don’t ever tell anybody.’ And he added, ‘If you’re really in trouble tell the squirrels. They’ll always find me and I’ll make sure you’ll be alright. So I wasn’t frightened because I knew I’d be alright. Wasn’t he a very clever man to do that? I think that’s maybe why my son studied psychology.”

Below: Jews being transferred into the Otwock ghetto, Poland 1940-41

PARTING

A few months later, Stefan found a place for his wife, working as a servant for a Christian family, and a separate hiding place for his daughters, with another Christian family. He paid these families to take the huge risk of sheltering his wife and children. He was also hiding 8 other relatives, paying for their stay, monitoring their situation, and moving them when things suddenly changed and it became too dangerous for them to remain. Plus staying in hiding himself while he worked for the Underground. It was a highly stressful juggling act where if one thing went wrong, the result was death.

When they first had to separate, Judy and Tosia wanted to know why they couldn’t go with their mother.

“One day God willing you will see your mother again,” Stefan said, trying to comfort them.

“Which God – the old one or the new one?” 4 year old Judy asked.

place of safety

The sisters, Judy and Tosia, lived in hiding for more than a year, moving about, changing their identities, learning to go to Church and to live as Christian children. Then in December 1941 the German secret police, the Gestapo, began operating near their latest hiding place.

An older cousin came to take them away. Izia was a 16 year old who had to think and act like an experienced spy.

The Gestapo captured another teenage cousin that day, and Izia had to have the presence of mind to run in and grab Judy now aged 5 and her sister Tosia aged 8.

They arrived at the railway station to see German soldiers shooting passengers in the ticket queue. Masking their reactions, the three girls boarded the train as if all that had nothing to do with them.

All Judy’s relatives who were in hiding nearby that day were captured or killed. This was the first of many of what Judy calls the “Little Miracles” that enabled her to survive.

THE CONVENT

Cousin Izia took the girls to their father. He had their hair dyed blonde, and found a place for them in the Sisters of Immaculate Conception convent in Warsaw. Despite its location opposite the SS headquarters in Kazimierzowska street, their activist Abbess, Sister Wanda Garczynska took in and saved a number of Jewish girls, as well as feeding Jewish children who crept out of the nearby Warsaw Ghetto.

Judy found the orderly convent very calming, and very different from the noisy kindergarten in the Ghetto. The nuns in their white habits, with blue aprons, seemed to her to be floating rather than walking; at the beginning she wondered if they were angels.

But while she felt safe in the convent with Tosia, life was also tense.

“I knew I was hiding something but I didn’t know what it was, what my secret was. If my sister wasn’t with me I probably wouldn’t have made it. She really really watched over me. Apparently one night I was singing a song which I often heard the orphans in the ghetto singing – Gib mir a shtikele broyt (Give me a peace of bread.) So she just woke me up immediately. She watched all the time. She also learned how to steal apples and bread, when we needed that later," Judy says.

NUNS

Poland had a large Jewish population and more Jews were both killed and rescued in Poland than in any other country during World War Two. Just to give you an idea, the figure for rescued Jews in Poland is generally put at 100,000 - 150,000.

Judy and Tosia Jablonski were among them.

Judy describes the nuns as extraordinary women. They were partnered with the Resistance, conducting many activities that carried the death penalty, including harbouring Jewish children, teaching history and other subjects forbidden by the Nazis and helping escaped Polish prisoners.

Sister Wanda set up a primary school and then a soup kitchen, to help hide all these illegal activities.

This video lists the nuns recognised by Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem in Jerusalem for their role in saving Jews during the War – including Sister Wanda.

The convent girls were aware of the danger. They took part in drills to prepare for surprise Gestapo raids. They learned to hide the forbidden books. The more Jewish looking children also had to learn to hide themselves, usually in the chapel behind the altar.

One Jewish girl, who’d arrived at the Convent saying 'I am Jasia and I have nobody' was taken in despite looking Jewish and having red hair – considered a give-away Semitic feature at that time. Once the nuns tried to dye her hair blonde, but it turned green, so when the German soldiers came, she and other Jewish looking children were hidden in the infirmary.

“Oh they used to be forever bandaged. They were supposed to have had mumps,” says Judy.

She and Tosia were not considered Jewish looking, so they were usually spared this, until they had to be moved from place to place.

“Then we’d have bandages around our faces. The German soldiers kept their distance because they were terrified of mumps. Apparently mumps affects your fertility if you get them as an adult … But at the time, when I was only 5 or 6, I didn’t understand why we had mumps so often,' Judy remembers.

WHEN LOVE MATURES INTO HEROISM

When Love matures into Heroism is the title of the life story Sister Wanda written by one of the nuns, Sister Maria Ena. It could equally describe the other brave women in their convent opposite the SS headquarters.

One incident that stays in Judy’s mind occurred in 1942 when German soldiers arrived without warning, and there was no time to hide Jasia, the red-headed Jewish girl.

“We were in a room, doing handicraft and mending socks and things when the German soldiers marched in. And a nun who wasn’t terribly old was sitting there, she was a big woman, and she shoved Jasia under her dress. She quickly pulled down her veil and wrinkled her hair and acted old, as if she couldn’t get up too easily from the chair. She was pretending to try and get up, when one German soldier said, ‘No you can sit’.

In her memoirs she wrote later that she could feel both their hearts beating, hers and Jasia’s, and that was the only sound she could hear,” says Judy.

“It was a miracle. Those little miracles all the time. No one would have survived if not for little miracles.”

Communion, 3 June 1943, The Convent of Sisters of Immaculate Conception Wasaw. Judy's sister Tosia is sitting to the left of the priest. She is not the only Jewish girl in this group. In fact, 4 out of the 7 girls are Jewish!

COMMUNION

The older girls including Tosia were preparing for their first Communion. In a convent this was the height of excitement, and also a distraction from the searches by German soldiers, the dwindling amount of food, and the bombs that were now falling regularly in the area.

While the girls finished their studies, a dress-maker visited to sew their Communion dresses.

Judy says she will never forget that Communion Day.

The 3rd of June 1943 dawned bright and sunny. Tosia and the 6 other excited girls had their hair rolled into Shirley Temple curls. They wore their special dresses, made of white silky material shot through with gold thread. A crown of white flowers was placed on their heads.

Judy's sister Tosia, front row, second from left. There are 3 other Jewish girls in the front row.

Judy thought Tosia looked beautiful. Remarkably, the majority of the girls taking their first Communion that day - 4 out of the 7 - were Jewish, which gives you an idea of how committed that convent was to saving Jewish children.

The ceremony passed in a dream, made magical by the appearance of Judy's father, Stefan.

FATHER

Judy’s heart almost burst with happiness. She loves the photos of her father with Tosia that summer day.

“It was such a wonderful day that I forgot the constant tension and feat that resided deep inside me.”

Judy's father Stefan looks down at his daughter Tosia, on the Priest's left. Stefan came to this Communion, but this was the last time they saw him.

After the communion Stefan took his daughters out to celebrate. It was the first time Judy had ever been to a restaurant. They ordered tomato soup with rice as a first course, Judy’s stomach gurgling in anticipation, till in an instant everything changed.

Two German men in dark coats came to their table and took Stefan away. Then a waitress carrying soup bowls came to serve the stunned girls. She spilt tomato soup on Tosia's white Communion dress.

“She leaned down to wipe the stain, and whispered ‘Run, children.’ Tosia took my hand and we walked – but did not run – out of the restaurant. As we passed the office, we heard a rasping voice shouting at my father. Tosia gripped my hand hard, we walked to the corner of the street, and then after that, we ran and ran.”

Judy never saw her father again.

FATHER'S FATE

Judy heard conflicting reports as to Stefan's fate, and only found out decades later, after writing her book, that he had been held in the political prison in Siedilce.

“When they picked him up it was as a political prisoner and for six months he was tortured, but they didn’t know he was Jewish. When they found out they took him to the cemetery and shot him there. That was one report. Another report was that he died in Auschwitz, all good witnesses but I don’t know what to believe,” Judy says sadly.

“All I know is that he was with me for the rest of the War and he helped me survive even when he wasn’t there. So you could say that he was there even when he wasn’t. When my sister told me that he was probably dead I was very angry and did not believe her. And even long after the War I’d run after men that looked like him. By the time I’d catch up and realise it wasn’t him, I’d lose him over and over again. It was years before I stopped running after strange men in the street.”

Judy's father Stefan, with his daughters and Father Ussas, on the last day they were together in June 1943.

Judy regards herself as a very lucky person but that doesn’t make up for the fact that she missed her father intensely as a child.

“My mother too, we all missed him. He was a wonderful man. In the end he saved eleven people. Eleven! Including five children from the family. My sister Tosia and myself and my cousin Lonia, who died recently, in her nineties. And her little brother Avram, and her middle sister Izia, the one who saved us at the railway station, who finished up back in Poland after the War. In fact the Museum of Jewish History in Warsaw was the brainchild of her daughter, Grazyna Pawlak” says Judy.

She pauses and adds, “I can’t tell my children enough how proud they should be to have come from this stock. And I can see my father in my own boys and girls.”

SUMMER 1943

When Judy and Tosia returned to the Convent on the night their father disappeared, her sister still wearing her soup- stained Communion dress, Sister Wanda decided it would be safest to send them away immediately, in case Stefan would give away their location under torture.

But he didn’t have to be tortured. His interrogators found a piece of paper with the address of the Convent among his things.

Anna Kaliska, who worked as a seamstress at the Convent, described what happened next in her account of her wartime experiences.

“An order came for Sister Wanda to present herself at Gestapo headquarters. A few days in a row she went there for interrogation. I remember her marching off with a determined look, carrying a large black umbrella, while we conducted heated, emotional prayers for her return.”

Sister Wanda survived the interrogations. Judy and Tosia were once again on the move, travelling with nuns along dangerous roads, having to avoid German military patrols, until they arrived at Willa Jutrzenka on the outskirts of Warsaw.

It was a grand old building, then run by an Ursuline order of nuns, wearing short grey habits and caps. Food was scarce and conditions spartan. More and more, the girls were put to work in the fields, doing men’s work. It was difficult for Judy, who was a weak malnourished 8 year old, suffering from blackouts and nose-bleeds.

THE GREY NUN WITH THE BLACK HEART

Judy remembers meeting her first unkind nun, who disliked and punished her. Judy dubbed her the Grey Nun with the Black Heart.

On one occasion the children were given honey, a rare treat as there was so little food, but the nun forbade Judy to have any saying it would be bad for her nosebleeds.

When she found that Tosia had brought Judy some bread with honey, in defiance of her orders, the nun grabbed Judy’s head, held it back and pushed her fingers down Judy’s throat again and again until she vomited up the bread and honey.

As the nun walked away, she said, “I told you it would make you sick.”

INSTITUTE FOR THE BLIND

Later in 1943, when bombing in the area became more intense, Judy and Tosia were moved to an Institute for blind children, in the forest at Laski. There they had to pretend to be blind, but they saw a boy eating boot polish, grass and ants, and when they were hungry, they tried the same foods.

“We soon gave up on the boot polish and grass, but we did have the occasional feast of ants, which tasted sour but not unpleasant.”

From there, when all the children had to be moved, they were taken in by a farmer’s wife. In return for board, they did cleaning chores. Then one day Judy saw a woman walking up the road to the farm.

“I closed my eyes, and opened them again to make sure I was indeed awake.”

It was her mother walking towards her. Judy and Tosia hadn’t seen her for more than 6 months.

“None of us could speak. We just huddled together in a threesome and stood like that for a long time.”

MOTHER

Their mother Fela went into town to organise to lengthen their shoes, now too small for their feet, and to buy them each a coat. She left again, promising they would soon be re-united.

By the winter of 1944, Judy’s mother had discovered another farm near Warsaw where the 3 of them could be hidden together and she came to take them.

“My mother was just something else. She was a feisty little woman. There was not much to her but by jove she could do anything. She attempted everything. Nothing set her back.”

Judy remembers that the farmer had trained a turkey to alert them to any German patrols. As soon as it spotted anyone in uniform it began making a fearsome noise. There was slightly more food there, and that along with the joy of being with her mother, was making Judy stronger. But just then her sister Tosia began getting weaker. They suspected diphtheria.

They didn’t know how to have her treated. The farmer’s wife agreed to take Tosia to a hospital in Warsaw. After ten days, Judy’s mother decided to visit her.

TOSIA

"My mother was on Aryan papers, so she dyed her dark hair blonde, painted her lips, put on a pair of spectacles that weren’t real – they were just window glass – to make her Jewish nose look smaller and she made sure she was smoking a cigarette so she looked like a prostitute and not a Jewish housewife. And dressed like that she took me with her to Warsaw to see Tosia,” Judy recalls.

“In those days German soldiers used to suddenly surround a street and more often than not shoot everyone who was out. It was their way of punishing the population when the Partisans carried out an operation against them. In Polish it was called Punkah which was like a catching game."

"And we were in the street there and my mother has got false papers that are easily identified as false and she’s got this child with her with no papers. And all of a sudden there’s Germans all around with guns. So she grabbed me by the hand and actually walked into the biggest most horrible looking one of them, bang, right into him. And she said ‘Oh please excuse me’ and he was so taken aback that he says ‘Madame’ and showed us through. Other people in the streets around us were rounded up and simply executed. And we got out.”

When they reached the hospital, Judy’s mother collapsed. Shaking and sweating, she had to sit on a stairway before she could compose herself to go up to see Tosia.

“But she survived, she was alright. I didn’t even think that she was strong. I just took it for granted that my mother could do anything.”

DEATH IS PART OF THE PROCESs

Judy speaks very casually about death. She says it’s simply because she was used to it.

“It was the norm, I saw a lot of people being shot. I even saw a baby being taken from her mother and grabbed by the legs and brain smashed against a wall, it was horrible. But being dead was also normal. I wasn’t frightened of dying.”

Russian soldiers

One morning early in 1945, when they left their apartment to look for food, their daily forage in the destroyed Polish capital, they heard Russian being spoken.

Judy saw a line of scruffy Russian soldiers, "not at all like the shiny German soldiers I was used to seeing,” and then saw her mother sink to her knees and start to cry, before grabbing the leg of the nearest soldier.

Red Army soldiers finally enter a destroyed Warsaw, January 1945

“Mamusia, Mamusia why are you crying, are they bad men?” Judy asked her mother.

Her mother hugged her and said, “No no darling, I’m crying because I’m so happy.”

To Judy’s amazement, the soldier was crying too.

That’s how she learned their war was over.

LIFE RESUMES

Judy’s mother Fela began trying to gather all the relatives who were left alive. First she found children she and her husband had been supporting in hiding. But other than the people they had saved, she found almost no one else. Their large happy pre-War family had all been killed.

The day Fela's brother Natan walked back in from a concentration camp, sick and skeletal, but alive, was exquisitely joyful.

Convinced there was no future for them in Europe, especially as Communism was establishing itself in Poland, Fela and Natan paid what we would now call people smugglers to take them to Germany, lying under parcels in a delivery truck. Then they had to climb over mountains at night - a huge effort for 10 year old Judy, carrying her favourite doll.

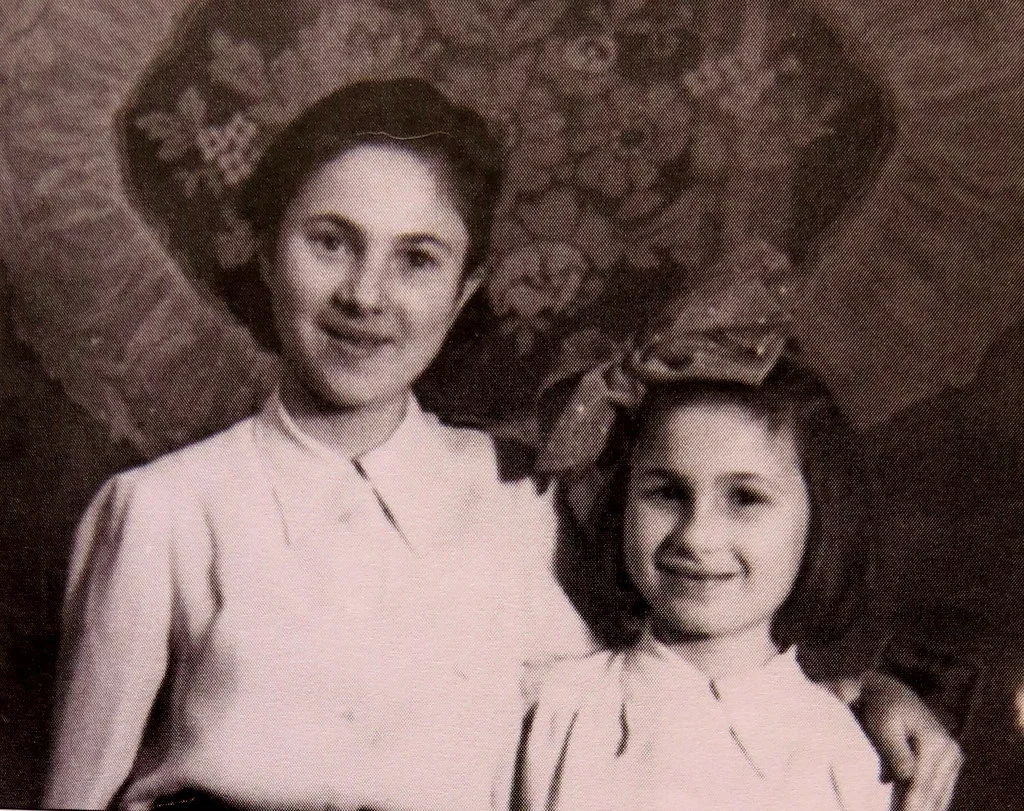

Below: Tosia and Judy in the Berlin DP camp at Schlachtensee. They are standing in front of their grandmother's bedspread, one of the few things their mother Fela had taken from her old home.

Once in Germany, they lived in a DP camp in East Berlin, at Schlaschtensee, and began applying for visas to the US and Australia.

They would wait for years.

THE CHILDREN WHO FORGOT HOW TO LAUGH

In 1947, the authorities put on a summer camp for the thousands of Jewish war orphans in their care. The planned highlight was a visit to the circus.

None of the children had ever been to a circus.

Below: Judy (left) with 2 friends, and also playing the accordion at the Berlin DP camp. She is around 11 years old.

Ponies, a dancing bear, acrobats and clowns – none could elicit a smile from them. They remained grave and wide-eyed. Judy remembers the clowns’ performance to this day, with fart jokes especially designed to make children laugh. But there wasn’t a squeak out of any of them.

“It was very difficult for the clowns and acrobats to do anything, because they got absolutely no response. But we were just too frightened to enjoy it. Hearing the German voices and you were free but you weren’t sure, were you really free? So no, nobody laughed. We didn’t know how as yet.”

Once they were safely back in the DP camp, they let their guard down giggling with each other about how funny the clowns had been. So they could play with each other, but remained cautious and apprehensive with strangers.

“You see I had a mother. Very few had a mother. And some of these children had come out of concentration camps. I had it easy in comparison to them. The fright was always there, the hunger was always there, the lice, the cold, the chilblains. My sister and I ate grass when we were hungry and ants, but we could get to the grass and ants."

Judy standing, reading aloud to the class, back left corner, Schlachtensee DP camp, 1947

HITLER'S BAKING TIN

Soon Judy was taking her first flight.

The changing reality of the Cold War meant that in 1948, American authorities moved all the residents from the Berlin DP camp, now in the Russian section of the city, and flew them to a new camp in another part of Germany, in the Western sector.

Landsberg was on the site of the prison where Hitler wrote Mein Kampf in the 1920’s. Judy’s mother rented a room in a house outside of the DP camp. It was their first “home” which was not behind barbed wire since the War ended 3 years earlier.

Authorities gave the family some provisions, including a blue enamel baking dish that was rumoured to be from Hitler’s retreat at Landsberg. While Judy says the whole town was probably full of items that had “belonged” to Hitler, she still has that baking dish, which they used for years.

AUSTRALIA

In 1951, when Judy was 15, they finally received their visas for Australia. After so many years, their US visa came through on the same day. They couldn’t choose and flipped a coin. Australia it was.

Family portrait taken in Europe before the trip to Australia: Judy's mother Fela and her brother Natan, seated; Tosia, Natan's wife Uschi and Judy, standing.

In autumn 1952, they sailed on the SS Napoli. Judy arrived in Melbourne in September 1952, on the day before Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement. She was about to turn 16.

FOOD

In Australia, Judy’s mother – “a brilliant cook” – cooked Polish food. Potato soup. Sorrel soup. Pickled cucumbers and herring. She made the noodles and dumplings she had been famous for in Poland. And also slow cooked meat dishes, including liver and giblets, when they could afford it. Judy learnt to prepare all these dishes, and still makes pickles and jams to her mother’s recipe, but now her repertoire also includes other dishes. But when it comes to giving out the recipes, that's more difficult. Like many of the Food is Love grandmothers, she works without recipes, and finds it hard to explain how she achieves her culinary results.

"With me it's like sprinkle flour, pour the water. I know exactly how much of each ingredient. Just think the taste, and you feel what it takes to make it. But to pass it on, it's necessary to measure what you put in.... " she says.

Every Thursday night dinner the whole family attends a celebratory dinner at Judy's.

Judy with her grandson Jonathan Green

Her large mezze table, with some Polish salads, some Italian, some Middle Eastern has something for everyone – the vegans, vegetarians, “pescetarians” and meat eaters in Judy's large family. There will be a main course fish and meat dish as well; and there is always a cake for dessert.

“Well you can’t finish a meal without a babka. Besides my son’s father-in-law always like a nice piece of cake to take home.”

Judy's Curried Lentil Soup

ingredients

1 large onion, diced

2 leeks with only outer leaves removed (use both green and white)

2 sticks of celery (leaves can also be used)

1 carrot

2 medium or 1 large sweet potato

¼ cup Persian red lentils or black lentils

¼ cup green lentils

¼ cup oranges lentils

1 tablespoon mild curry powder (less if hot curry powder)

½ kilo fresh or 400g diced tomatoes undrained

For vegetarian: 1 tablespoon vegetarian stock powder and 3 or four bay leaves

For meat eaters: generous handful smoked veal ribs

Salt and Pepper

METHOD

1. Put a little oil in a heavy based 7 litre pot and sauté diced onion until golden. Take off heat and stir in curry powder

2. Roughly dice carrot, celery and leeks. Add to pot and return to cook, stirring over a small flame.

3. Cut sweet potato into chunks and add to pot. Pour in boiling water/stock until the volume of mixture is tripled. Add lentils and tomato (if using fresh tomatoes, dice first).

4 If making vegetarian, add bay leaves and mixed Italian spices; if cooking for meat eaters, add veal ribs.

5. Cook gently for 60-90 minutes. Just before removing from stove, add 2 tablespoons of vinegar. Add salt and pepper to taste and serve.

SYDNEY TEST KITCHEN

In wintry Sydney, Miyuki Mane made the lentil soup, although her family eat lentils a few times a year at most.

“My daughter was watching a health documentary saying we all need to eat more lentils as they're good for our hearts, and the next day I got your email. So I thought why not?”

She says the soup was absolutely delicious and easy.

“I had most of the veggies except leeks, and I added cumin, thyme, garlic, diced white radish, and kale at the end. I want to add a bit of chili to make it spicy next time, or more curry powder? I see that you can adjust the flavour to whatever you like with the spices and different vegetables.”

VERDICT

"There couldn't be a more perfect comforting winter meal, especially as my daughter is mostly vegan and my husband is GF. She had it with toasted sour dough. They both loved it and couldn't have enough of it. If my son was home, I might have added a boiled egg as well. Make this soup!"

MELBOURNE TEST KITCHEN

In Melbourne Amanda Hampel also made the soup. She couldn't find black lentils so she used red, green and yellow. She didn't have any curry powder and used 4 bay leaves (no stock or meat).

Amanda has a personal health issue with lentils, but she is a superstar, prepared to cook what she can’t eat!!!

“It smelt amazing while it was cooking, really easy and quick recipe to follow! I had some family over that afternoon so dished it up as afternoon tea and they loved it! Full of flavour. It was perfect without the stock too. A real meal in a bowl. My dad had it last night and loved it too ;)"

VERDICT

This is definitely not a recipe for me to adapt to be able to eat myself, so can't say I was able to try it personally, but from the smell & look, and the reax from the family, thumbs up from me!!”

And from Jerusalem, I want to add my thumbs up here, since my mother has been visiting, and I made it for her, completely forgetting that she doesn't like lentils. Doh! But it was so tasty that she loved it! It was better the second day, of course, when the flavours became more pronounced, and I would add even more curry powder and some chili -- but then I like things hot. Great, easy, tasty soup!

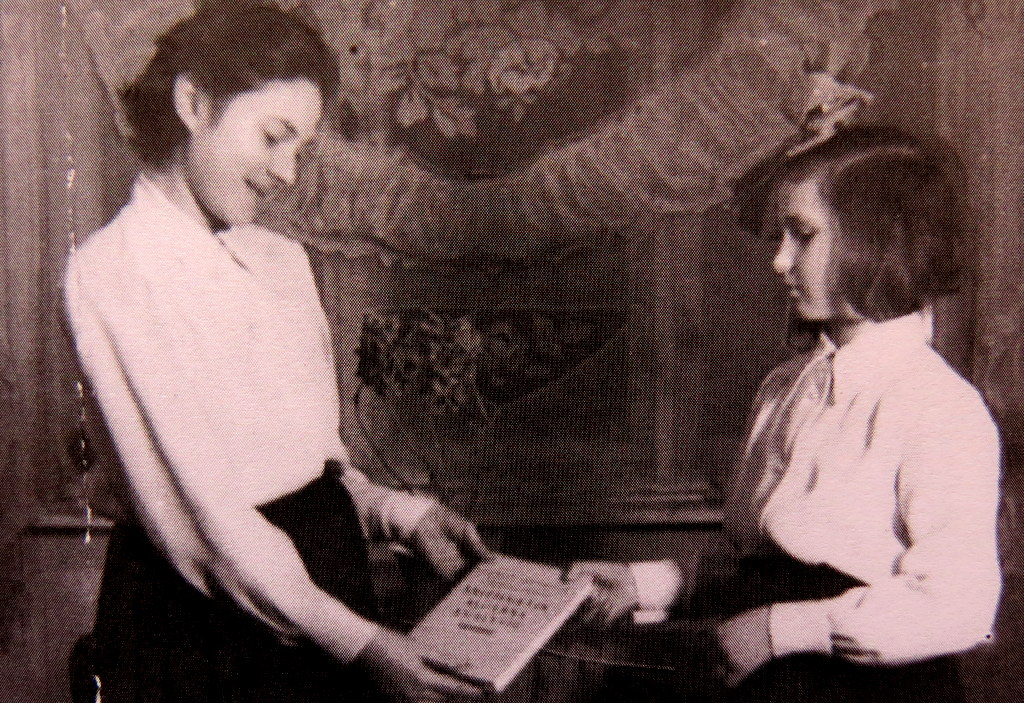

Aviva checks a recipe with her grandmother, Judy Kolt

Baked Fish with Harissa

INGREDIENTS

750g any firm white fish, in fillets

1 ½ lemons, juiced

1 heaped tablespoon mayonnaise (not sweet)

½ cup chopped flat leafed parsley or basil

Harissa – buy it pre-made, or mix the following spices: Cumin, turmeric, paprika, coriander, cinnamon, nutmeg, salt, black pepper, chilli pepper

METHOD

1. Wash and dry fish. Cut in to mid-sized pieces

2. Roll in lemon juice, and place flat in single layer in a pyrex baking dish, with the juice

3. Sprinkle with Harissa. Cover with mayonnaise, mixing with fingers to ensure fish is covered on all sides. Sprinkle with parsley or basil.

4. Marinate for a least 1 hour. Bake for 15-20 minutes at 200°C.

JERUSALEM TEST KITCHEN

My mother got both barrels, the soup and the fish, almost a mini-me Judy Kolt Friday night table ...

We both loved both dishes. I followed Judy's recipe faithfully, marinating and baking the fish, and the result was great. Tangy, spicy and light. And very easy.

I was a little hesitant about the mayonaise, since I have never baked with it before, but it worked a treat. I usually like making my own, but didn't have time this week, so I can report store-bought works well, and makes this a very quick dish. Mayo from the fridge, harissa from the fridge, just juice a lemon and you're basically done. I mixed basil and coriander leaves and I think you could bake it for much less than 20 minutes. In my hot oven, 10-15 would do.

SYDNEY TEST KITCHEN

In Sydney, Judy Ingram used snapper fillets, and kept them large.

"I forgot to marinate, and didn't have all the spices, but it was a treat! And OMG, easy!"

Judy made a mix of mayonaise and French mustard to which she added a little harissa paste. She had sumac at home, so sprinkled some of that in too. Judy was in a grilling mood, so she went with that instead of baking.

"I grilled it for about three minutes each side I served it with sweet potato, fried onions and salad and it was delicious!"

It's become a favourite in Judy's kitchen, and the last time she made it she grilled for 7 minutes on one side - mayo side up. "And that was dinner! Too easy."

LOVE STORY

Five years after arriving in Melbourne, 21 year old Judy Jablonska met Hymie Kolt. He was the son of Jewish migrants from Russia who'd spent the War in Australia and Judy first saw him on a motor bike in 1956. She liked what she saw. Then he asked her out and she "knew" from their first date.

"He arrived in this beautiful big car. I was quite disappointed I rather liked the motorbike. And he took my arm and took me across the road to the car and I felt so safe and secure that I sort of knew we were going to get married. And then I let him chase me until I caught him," Judy laughs.

Judy marries Hymie Kolt, Melbourne 1957.

"He was a very beautiful person and he really was the best friend I ever had and a very good husband and a most interesting person to live with. Never a dull moment. People went overseas on holidays and did wonderful things, we went camping in a tent. I was terrified of it at first because I didn’t know how it would go. But it was brilliant. The kids loved it, I loved it. We never did anything the way normal people did."

"You’d never know today what we were going to do tomorrow. It was a very exciting life. And he was a great influence on these children who never did anything without father’s approval and we didn’t do much without the children’s approval either."

Judy lived happily with Hymie until his death more than half a century later.

"It’s very very sad without him but I’m not complaining because we were so lucky to have 56 good years together. But it’s bloomin' lonely. I mean we argued like cats and dogs and the making up was wonderful. We never argued badly enough to really dislike each other. We had different personalities but we had a fantastic life together."

'THERE'S NO RELAXING'

Looking back, Judy says her saving grace during the War was that she was so young.

“This was simply life, I didn’t know it could be better. That’s why I always feel so sorry for the people who were older, and I cannot understand how they could manage to live a normal life afterwards. Because to me that was normal life, I didn’t know any different.”

Judy says this life experience has made her a good judge of people.

“And those that I judge I trust. Because you’ve got to trust somebody. You can’t live in fear.”

But Judy has experienced a lot of unnamed terrors all her life, and years later was afraid of walking in the dark in Melbourne, in her own garden.

“You see a shadow behind a tree, and you just don’t know whether the shadow is going to come out and hit you on the head or shoot you or whatever or put you in a camp. There’s no relaxing. And it’s very hard to get rid of that. But you mustn’t let it get to you.”

When I comment that she is resilient, Judy says every person finds resilience within them if they need to.

“You’ve just got to trust yourself. And I guess I didn’t understand enough to be broken.”

Fela with her daughters Judy and Tosia. Landsberg, 1948