FESTIVAL OF LIGHT

At this time of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, as we head to the shortest day of the year, you can see the need for a festival of light.

It’s spiritual, of course, but also physical.

In Jerusalem, an oil based menorah, lit outside the house has become increasingly popular in religious areas over the past decade.

You need a pinpoint of light to inspire you and to distract you from the dark and the cold. It’s beautiful to walk through the freezing streets and see the candles lighting up the night, and ‘protecting’ each home.

It’s also the time of the year when you want carb-heavy food and whether you long for it or not, the Festival of Hannukah is also about fried food.

So today here’s a recipe for the traditional Hannukah food par excellence, the fried potato Latke. It’s from our book Just Add Love, Holocaust Survivors Share their Stories and Recipes, from Thea Riesel whose remarkable story is below too.

(You can order your copy of Just Add Love here on this website. It makes a beautiful, meaningful holiday gift.)

We’ll also put out a recipe a day during Hannukah for other vegetable fritters, also from the book, including leek (prasa) fritters, a Sephardi take on the potato latke, vegan zucchini fritters and more. It may be time to break out the Dutch herring cakes too!

THEA RIESEL

Now in her 90’s, Thea was born in Vienna, and has lived most of her life in Sydney, Australia, where she is matriarch of a family of 3 children and numerous grandchildren.

Thea Riesel with her grandson Jono

She was a promising violinist, and was lucky enough to be in Indonesia with her parents during World War Two, which enabled her to avoid the death camps of Europe. But she and her parents were interred instead in Japanese prisoner of war camps for more than 2 years. Thea emerged weighing 40 kilos, and no longer able to fulfil dreams of being a concert violinist. The war had interrupted her playing for too long.

“I wouldn't call this a hard life,” says Thea. “I know what I was spared, and it could have been much, much worse.”

Her story appears in the book along with that of her best friend Mimi Deitz.

Thea Riesel and Mimi Deitz

FRIENDSHIP

Thea Riesel and Mimi Deitz have been friends for more than 75 (!) years.

They slept in adjoining bunks as teenagers in a Japanese prisoner of war camp during World War Two, and today when both are in their 90s, they live around the corner from each other in Sydney. They are mothers and grandmothers - Mimi is a great-grandmother - but their longest relationship is with each other.

“Mimi became my friend before the Japanese came to Indonesia. She’s my friend till today, and she is the real cook. She is still baking yeast cakes, I don’t know why you're wasting your time with me!” Thea said, the first time we spoke.

THEA RIESEL

Thea is precise, punctual, rational, organised, tidy – all the ‘Germanic’ qualities, even though she left Vienna as a child, and has lived for most of her long life, seven decades now, in Australia.

When Europe became dangerous for Jews in the 1930's, her family was able to escape to Indonesia, then known as the Dutch East Indies, where her father had worked as a young man.

Thea's parents with her as a baby in Indonesia

“In 1939, they opted for Java. This was a decision that would save all our lives,” says Thea.

There were only about 3,000 Jews out of 68 million Indonesians in what was then known as the Dutch East Indies. For this handful of people, it was a sanctuary.

MIMI DeiTZ

Mimi is a smiley woman, calm, practical and kind. If there is an opposite to a drama queen, Mimi is it. Her vision is poor now, but she's always positive, with her sense of humour intact.

Mimi Deitz with grandson Levi

Mimi was also born in Vienna, but the two met for the first time as schoolgirls in Indonesia, after Mimi and her family were able to escape.

“In Germany it started slowly, from 1933. For us in Austria, it came all at once, as soon as Hitler annexed Austria in 1938. Suddenly Jews were forced to scrub the pavement, on their hands and knees at the feet of German soldiers. I saw that personally,” says Mimi.

“I remember German soldiers, or maybe they were Gestapo, knocking on the door, to take my father to the Dachau concentration camp. He wasn't home, so he escaped that time. My aunt who was in Indonesia got us a visa. We left in November 1938. I am not sure if it was before or after Kristallnacht, the attack against Jews across the German Reich, which began in early November.”

Mimi set sail with her parents and brother. They reached Batavia (Jakarta) in January 1939.

Mimi as a child in Vienna, with her brother Gert and her parents, Nandor and Toba Braun

NEW LIFE

Mimi and Thea met at school and became firm friends. When Thea wasn't practising her violin, they rode their bikes together.

“Life was good for us, just when it was getting very bad in Europe,” says Thea.

Mimi's 1939 ID papers, issued by Dutch authorities in Java. Mimi is 13 years old in this picture.

JAPAN INVADES

The good times ended in March 1942 whenJapanese troops overran Indonesia. The first impact the girls felt was that there was no more school.

“Study was forbidden. It was Japanese policy. I was happy at first, as I had more time for my violin. I practised every day,” says Thea.

ATTITUDE TO JEWS

“The Japanese were friendly to the Jews. Curious, respectful. There were also very few Jews, relative to the population – 3,000 out of 68 million is not a lot!” says Thea. "They considered us to be semi-Asiatic, with the result that we were lumped together with half-caste Indonesian civilians, and were not immediately arrested."

But Japan and Germany were allies. Under pressure from the Nazis, the Japanese began moving Jews to prisoner of war camps, along with other European civilians.

In early 1943, Jewish men were rounded up. By late 1943, it was the turn of Jewish women and children, including Thea and Mimi and their mothers.

“In August or September 1943 we were told to lock up our homes, and go to the police station, with our keys and valuables. We were told to bring ‘only what you could carry’. I left my violin behind,” says Thea sadly.

They handed over their keys and valuables and the women were taken away in a train with blacked out windows. Thea was aged 19, Mimi 18.

PRISON CAMPS

130,000 civilians were held as prisoners in Japanese camps in Indonesia during World War Two. More than ten percent of them - 14,000 - would not survive, succumbing to starvation and disease.

Thea and Mimi were in 3 different internment camps over the next 2 years. The first camp was Tanah Tinggi.

Semarang women’s camp, 1945, photo Drakulic and Schreiber.

TANAH TINGGI (high earth)

Previously a prison for young offenders, the camp was stiflingly hot and dirty, with cockroaches, rats and swarms of flies.

"There were hundreds of people, maybe 1,000. We arrived as a Jewish group, to join the British, Australian and Americans who were already there. It was a mixed camp, and we were on the women’s side,” says Thea.

They were watched over by 2 sets of armed guards, Japanese and Indonesian. They were sometimes beaten for no reason.

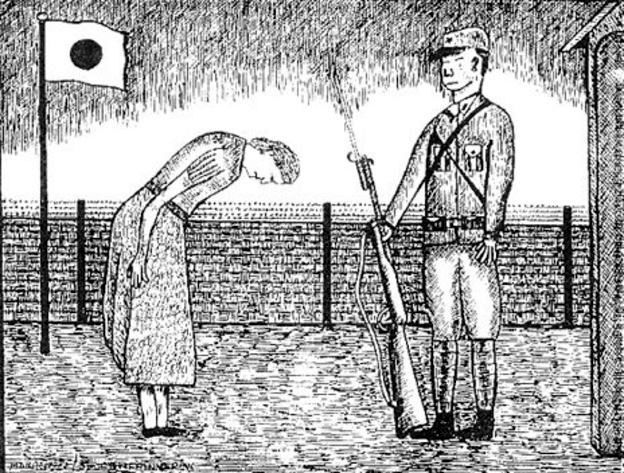

“There was a daily flag raising ceremony, called Tenko, where they played the Japanese anthem and we had to count off and bow to the Japanese flag,” says Thea. "We had to bow to any Japanese soldier we met, and to the Indonesians as well."

Women bowing to the Japanese flag at a POW camp. 130,000 civillians were interred in Indonesia during WWII.

“There was a large outdoor space, and planks around the walls inside the barracks. It was overcrowded, and unhygienic. We weren't too short of food at the start, but bit by bit we got hungry," says Mimi.

“This is how we slept. Imagine a room. A hall, with bars on the windows. Along the sides there are planks perpendicular to the wall, 55 cm wide. Those who went with mattresses cut them down to fit the planks. Otherwise you slept directly on the plank. There were bed bugs or other insects that bit you while you slept. People cried out ‘I’m hungry’ in the middle of the night,” Thea recalls.

"Bed bugs smell when you kill them. That's how you know you've succeeded," Thea says matter of factly.

FOOD

Both speak at once about food.

“We didn’t cook, the Indonesian prisoners cooked for us. They sent 2 big drums to the rooms. One was coffee, that was in the morning. The other was mostly rice. Rice, corn kernels - and weevils!"

“As we got hungrier, we sat there exchanging recipes. I collected them, and had them for years. I only threw them out when I moved to this apartment 5 years ago,” says Mimi.

After 6 months, when the Japanese announced the prisoners were to move, Thea was happy.

“I said, ‘Thank God we are moving!’ But the British women said, ‘Don’t say that, it never gets better.’ And they were right, the next place was harder.”

TANGERANG

Tangerang was worse.

“It was even more crowded, there were more prisoners, thousands, but now less food. It was a camp for women and children, so they separated the boys, taking boys aged 16 away to the men’s camps. Then they took them aged 15, and by the end, they were taking 13 year old boys away from their mothers, it was heartbreaking,” says Thea.

Discipline was harsh. Prisoners who did not bow sufficiently to Japanese soldiers were beaten. All prisoners were forced to stand in the sun for hours to take responsibility if any one of them breached the rules.

The picture on the left is a sketch by a prisoner; on the right European children behind bars, in a Japanese internment camp, 1946. (Copyright: Drakulic and Schreiber)

“There we had to do our own cooking, and all other duties. People fought to be in the kitchen and the vegetable garden,” says Thea. "You were not allowed to take food, but you could eat a tomato or cucumber when you were out there."

Meals consisted of only one scoop of food, decreased from three times to twice daily. This was near-starvation rations. Women stopped menstruating and children's growth became stunted.

“Illness was rampant. There was Malaria, cholera, beri-beri and dysentry," Thea recalls. "People got horrible skin ulcers, caused by the climate, which could kill you. That’s what almost happened to Mimi.”

MIMI’s illness

“In Tangerang I became very sick. I got all my diseases at the same time. Malaria, dysentery, and an infection, which started in my teeth, moved to my gums and then my whole body. My white blood cell count was very low. I was very nearly gone.”

Thea remembers the whole camp praying for Mimi.

She was so close to death that the doctor had already given the nurses instructions for what to do with her corpse. At the last moment, the doctor gave her a dose of sulphur. To everyone’s surprise, Mimi rallied.

“What saved me were the Red Cross packages. I don’t know if antibiotics were available in Indonesia at the time, but there weren't any to be had. Still that sulphur did the trick, and I pulled through,” says Mimi.

The girl they’d given up on kept living.

“After I’d been sick, the camp management put me on kitchen duties. That was an act of kindness. There I could eat a little more and that helped. Still, when we were liberated from the next camp, I weighed 42 kilos and my mother weighed even less - 38 kilos.”

Mimi pauses.

“If you want to know more details, you have to ask Thea, she knows more than me.”

“The reason Mimi can’t remember much is because of how sick she was. It affected her memory,” Thea explains.

"No that's not true, Thea! I just always had a bad memory," says Mimi as they bicker for a moment over their memories.

Food preparation in Semarang women’s camp, 1946, (photo Drakulic / Schreiber)

train

Thea and Mimi and their mothers survived at Tangarang for about 12 months. Around March 1945 they were moved again, and the train journey to the final camp is one of Mimi’s worst memories.

“They locked the doors and windows of the train, and it was hot, stiflingly hot, and I couldn't get enough air and thought I would suffocate. That was a truly traumatic moment,” Mimi recalls.

The girls spent the last months of the war at Adek camp on the outskirts of Jakarta. By May 1945, Hitler had been defeated in Europe, but the War in the Pacific dragged on. As losses mounted, rations decreased. There was growing hunger, disease and exhaustion.

AUGUST 1945

On Thea’s 21st birthday, 6 August 1945, the US dropped an atomic bomb on Japan.

“We didn't know anything about Hiroshima. The Camp administration came out, the Japanese officers in their beautiful uniforms, and polished shoes and they had to eat humble pie, and apologise to us and tell they had been defeated,” says Mimi.

It was so sudden there were no Allied troops to take over the camp. The prisoners remained there with their jailers.

“The Japanese promised to look after us till the Allies arrived and they kept their word. They told us not to leave, for our own safety. The Indonesians were bloodthirsty after the War, feeling this was their chance for Independence. Western women on their own were at great risk at that time," Thea explains.

PERSPECTIVE

Thea and Mimi and their families survived the War. They were sick and thin – but alive. For both girls, the reunion with their fathers, after years apart, was "pure joy."

Thea reflects on her experience as a prisoner.

“The Japanese were brutal in China, and Burma, and slightly better with us. I don’t want to pretend it was easy, it wasn't, but it was not the worst experience any human has undergone. You see, I knew what was happening in Europe. We’d met Jews from Germany and they’d told us. I knew it was worse there,” says Thea.

Despite her own brush with death, Mimi agrees that they did not suffer too badly. She stresses that everything is relative.

“Life is very strange isn't it? You can’t make predictions. After the war, the Americans were dropping Red Cross food parcels near the Camp for us. First they dropped leaflets telling us where the area would be, and everyone was so excited when the first box landed. But then there was a mistake and a box hit a woman and killed her. Imagine surviving the war to be killed by a Red Cross package afterwards …” says Mimi.

AUSTRALIA - MIMI

In 1946, Mimi went to Australia for medical treatment. After an operation removing and replacing all her upper teeth, she moved to Sydney - and stayed.

In 1949, when she was 23, a friend introduced her to another Jewish migrant, Victor Deitz.

“He was 26, born in Cairo, to a Russian father, and a half Russian mother. They spent the war in Cairo, which was then under British control. We’d had very different experiences, since he spent the war in ‘British freedom’, but something clicked because we started going out, and 8 months later we were married. That was 1950,” says Mimi. “We bought a milk bar in Lidcombe in Sydney and lived above the shop. Then we bought a shop in Burwood, a tobacconist, barber and sporting goods. Victor was a wonderful husband and a devoted father.”

Mimi and Victor Deitz and their 3 children, David, Susie and Peter

AUSTRALIA - THEA

After the war Thea and her parents returned to Europe. She studied in Holland for 5 years, before following Mimi to Sydney in 1951. She quickly found work.

“Getting office work in Sydney was easy. Everywhere I applied they said can you start tomorrow? I said, I’ll let you know. That’s how it was in 1951."

Shy and particular, Thea didn't marry immediately. In 1955, more than 3 years after arriving in Sydney, Thea met a German Jewish migrant, Fabian Riesel.

“It must have been right. I was 31 and Fabi had his 40th birthday during our honeymoon and neither of us had been married before. What did I like about him? He was sympatische, easy to talk to. (I'm glad the word ‘simpatico’ has become part of the English language – it was missing.) I didn't feel nervous when I was with him. I was happy. We became engaged after only 5 months, even less. He asked me to marry him in August and straight away I said yes, I was waiting for the question.”

It was only after they were engaged that Fabi told Thea that he wanted to keep a kosher home. Thea was not from a religious family.

“I was sufficiently in love not to protest, to say alright. So I guess to answer your question, I must have loved him.”

Thea always cooked for Fabi and their family, a daughter, Ruth, and twins Mark and David. Her scrumptious latkes are good at Hannukah, or any time of the year, and are served in the European way - with savoury rather than sweet toppings. (Applesauce is an American invention, it seems!)

Potato Latkes

Serves 6 INGREDIENTS

1 ½ -2 kilos / 3-4 lbs potatoes. Old potatoes, the older the better. "In Europe we used the old, old ones, that had been under the house since the last winter. We can’t get them like that here," says Thea

1 medium onion

4-5 eggs

1 cup breadcrumbs or matzo meal. Best to start with ½ cup and then keep adding.

Salt and pepper

METHOD

1. We're only on the first step and it's already controversial. Thea peels the potatoes. Her daughter-in-law doesn't, so we did one lot peeled, and one unpeeled, and both were fine. They do look more uniform if you peel them, but you can cut this step out to save time.

2. Grate the potatoes. Thea maintains that grating by hand produces a better latke – and most other Just Add Love grandmothers agree with her. It is however much more work, and to save her grandchildrens’ elbow grease, Thea agreed to put one lot into the food processor, using the fine blade setting.

3. Grate the onion the same way, then transfer the lot to a large bowl.

4. Let stand 15 minutes or until water forms, then squeeze the potato-onion mix to drain. You can do this using your hands or gather up the whole lot in a towel and squeeze that way.

5. Add the eggs, and the salt and pepper and mix. Add half a cup of breadcrumbs, and mix again. Keep adding until the mixture is no longer sloppy. NB: You may find if you didn't squeeze out enough water earlier, you will have to do it again, or add more bread crumbs. Both options are fine.

6. Form into small oval shaped patties, the size of your palm, and deep fry in a neutral oil. Turn over once, remove and drain on paper towels.

Best hot, straight out of the pan. Otherwise, eat warm. These are incredibly tasty for so few ingredients.

GOOD FORTUNE

Last word goes to Thea and Mimi. Like all the grandmothers in this book, they don’t complain, despite all they endured, and in fact don’t consider that they had a hard life.

“If I’d stayed in Europe, I would certainly have lost my parents. They would have been straight away taken to the gas chambers. And I could easily have been killed too. My cousin who was going to be a concert pianist, she went up in flames," Thea sighs. "So yes, I suppose I have been lucky."

Echoing Thea’s world view, Mimi also sees her good fortune in life.

“I was not traumatised in the camp, the biggest difficulty was that we didn't know when it would end. Once my health improved, it was behind me. I don’t think the fact that I was hungry for that long time affected my relationship with food. The repercussions really were that I had no education. When I look back that would have made a difference. I don’t think this was a hard life.

Mimi and Thea on a bus in Sydney. You can read more of their stories and find more of their recipes in our Book Just Add Love - and order it on this website.

p.s. SWEET

It’s funny how a miracle where one day’s supply of oil lasted for 8 days at the Temple in Jerusalem should turn into a religious ritual of eating fritters and doughuts!

In Israel, doughnuts are big. In fact, the humble doughnut has undergone a revolution.

Light, fried dough balls - ponchikes, in Yiddish or sufganiyot, in Hebrew - were once filled with jam or at most dulce de leche. You can still find those, just, but front of the cake shop cabinets these days are their glammed up sexy cousins filled with rich chocolate, fruit and alcohol-laced creme patisserie and nut fillings, in rainbow colours, covered with shiny toppings and often served with a small vial of liquid flavouring which you inject just before serving.

I am not a big doughnut fan - give me Mimi’s chocolate yeast babka any day - but it’s worth visiting Jerusalem just to see the displays in the bakery windows. They are definitely Instagram ready! I might go and do a little taste test for you during this holiday :-)

Happy Hannukah to everyone, may all our lives be filled with light.